Opening 16/05 - 17/05 - 26/07, 2024

intergenerational forms

Curated by Eleonora Milani

Carla Accardi, James Bantone, Becky Beasley, Pascale Birchler, Azize Ferizi, Sheila Hicks, Simone Holliger, Deborah-Joyce Holman, PRICE

I remember the opening of David Joselit’s Notes on Surface quite vividly. I found it absolutely brilliant. The inspiration for his reflections on surface was the sight of a billboard in his neighborhood in Los Angeles advertising elective plastic surgery. What struck him was the following quote: “Real? Who cares!” Ruling out the possibility that the reader might be even remotely able to associate the world real with Lacanian real, he focuses on the meaning of authenticity that the word suggests. But if being authentic is relatively important, since medicine has shown that bodies are malleable, Joselit wonders where the self-dwells, and whether it is not to be found in the changing surfaces of the body. Although the text opens a dense consideration of flatness by going through Jameson and Greenberg (extremely interesting for lovers of postmodern art criticism like yours truly) it is in this question of the author’s that I find the deepest meaning. Just as the real is for another great American postmodern theorist, this mutability of the surface and of forms is possibly retroactive.

Only recently have I been taking a close look at Carla Accardi’s work from the turn of the 21st century and realized that Joselit published this text in the year 2000. Coincidence, or maybe not. I have started thinking about those large canvases, those signs that opened up until they almost disappeared, until their incisiveness faded. Without rules of composition, the relationship between signifier/meaning and form/color is now a memory linked to previous productions. On a different level, Sheila Hicks’ works exude constant tension in both the 2 and the 3D levels because they deceive traditional media categories. In her surfaces, that are made of primal forms which do not resemble any representations – this is typical of the early artistic Avant-gardes – Hicks renegotiates form by forcing the idea of an abstractionism that fails to conceal the manipulation of a living material such as fabric, as well as the bodily and material element. In those forms, which are amorphous, explosive, and full of color, I felt a freshness that is common to the Millennial vibe, of which I am a product, and which brings me closer to a certain way of looking at form, the body and representation in a broader sense.

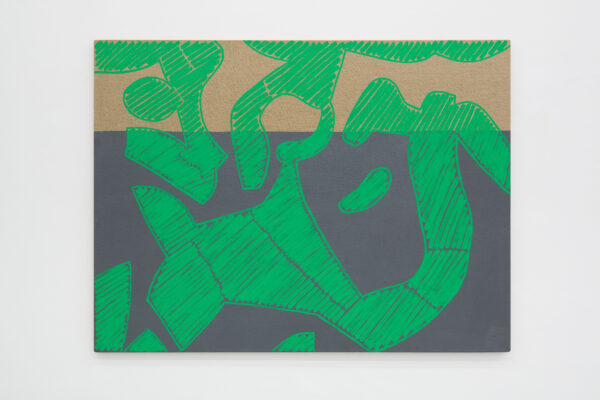

How can research as systematic as Accardi’s and Hicks’s come close to that of a generation that is still so sociologically debated, and which looks at the things of the world with a visual acceleration that has no precedent? It is in the use of form that the glue for this is found, a form that crosses generations without pigeonholing or caging itself into pre-constituted definitions. Carla Accardi’s Verde e Grigio scuro (2000) and Sheila Hicks’ Convergence ardoise (1996), are somewhat like the scent of this group show, which, without any theoretical or thematic pretense such as that which a more canonical approach would have, is an attempt (or attempts) to look at the possibilities of form through distant generational languages that coexist in the total freedom of the use of sign, form, and body.

The sign and formal multifacetedness that emerges in the practices of historicized artists such as Accardi and Sheila Hicks in dialogue with the more contemporary languages of James Bantone, Becky Beasley, Pascale Birchler, Azize Ferizi, Simone Holliger, Deborah-Joyce Holman, and PRICE – almost all Millennials like me – goes beyond the purity of the media and inhabits a liminal zone in which the figure, self-representation, volumes, and image are liberated. Uprooted from all sources and locations as they are, Bantone’s corporeal mannequins end up being swallowed by surfaces, by colours and by layers of reflection on the power of the body. In contrast, Birchler’s self-portrait makes us reconfront uncomfortable questions such as self-scrutiny: which forms of identity will stand the test of time? By simulating a monumentality which implodes systematically, Holliger’s volumes find comfort in a fragile and perishable material which is complimentary to Ferizi’s sculptopainted forms. Ferizi finds new impulses towards the artistic object which presents itself directly, without any altering of reality. In contrast, Beasley’s sculptural research rethinks the intimacy of inhabiting space through silent and often muscular objects. Holman returns to his work on signs carefully returning them under the form of identity and historical memory. This is a way to confront the conflict between socially normative categories which in PRICE’s protean practice resolves itself in imposing architecture which ridicules the white cube or in effluvia which work on the absence and the smell of the form.

In this way, those forms which have inspired the exhibition become disconnected from signs, and by opening up to a polymorphism which transcends recognizable geometries and hierarchical criteria, surprisingly connect themselves to the sensitivity of the youngest generations, who willingly make themselves the game of the object, of the form and if its coexistence in space and time.

Eleonora Milani

Curated by Eleonora Milani

Carla Accardi, James Bantone, Becky Beasley, Pascale Birchler, Azize Ferizi, Sheila Hicks, Simone Holliger, Deborah-Joyce Holman, PRICE

I remember the opening of David Joselit’s Notes on Surface quite vividly. I found it absolutely brilliant. The inspiration for his reflections on surface was the sight of a billboard in his neighborhood in Los Angeles advertising elective plastic surgery. What struck him was the following quote: “Real? Who cares!” Ruling out the possibility that the reader might be even remotely able to associate the world real with Lacanian real, he focuses on the meaning of authenticity that the word suggests. But if being authentic is relatively important, since medicine has shown that bodies are malleable, Joselit wonders where the self-dwells, and whether it is not to be found in the changing surfaces of the body. Although the text opens a dense consideration of flatness by going through Jameson and Greenberg (extremely interesting for lovers of postmodern art criticism like yours truly) it is in this question of the author’s that I find the deepest meaning. Just as the real is for another great American postmodern theorist, this mutability of the surface and of forms is possibly retroactive.

Only recently have I been taking a close look at Carla Accardi’s work from the turn of the 21st century and realized that Joselit published this text in the year 2000. Coincidence, or maybe not. I have started thinking about those large canvases, those signs that opened up until they almost disappeared, until their incisiveness faded. Without rules of composition, the relationship between signifier/meaning and form/color is now a memory linked to previous productions. On a different level, Sheila Hicks’ works exude constant tension in both the 2 and the 3D levels because they deceive traditional media categories. In her surfaces, that are made of primal forms which do not resemble any representations – this is typical of the early artistic Avant-gardes – Hicks renegotiates form by forcing the idea of an abstractionism that fails to conceal the manipulation of a living material such as fabric, as well as the bodily and material element. In those forms, which are amorphous, explosive, and full of color, I felt a freshness that is common to the Millennial vibe, of which I am a product, and which brings me closer to a certain way of looking at form, the body and representation in a broader sense.

How can research as systematic as Accardi’s and Hicks’s come close to that of a generation that is still so sociologically debated, and which looks at the things of the world with a visual acceleration that has no precedent? It is in the use of form that the glue for this is found, a form that crosses generations without pigeonholing or caging itself into pre-constituted definitions. Carla Accardi’s Verde e Grigio scuro (2000) and Sheila Hicks’ Convergence ardoise (1996), are somewhat like the scent of this group show, which, without any theoretical or thematic pretense such as that which a more canonical approach would have, is an attempt (or attempts) to look at the possibilities of form through distant generational languages that coexist in the total freedom of the use of sign, form, and body.

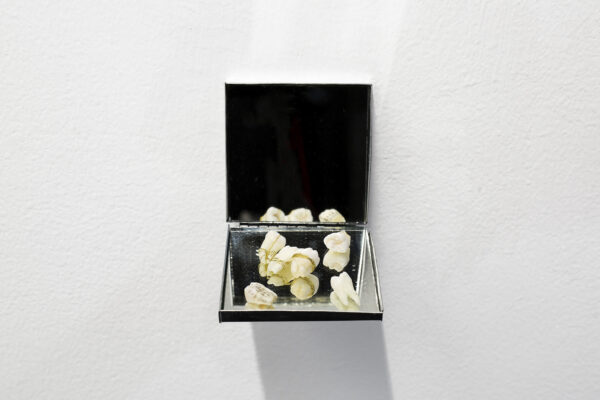

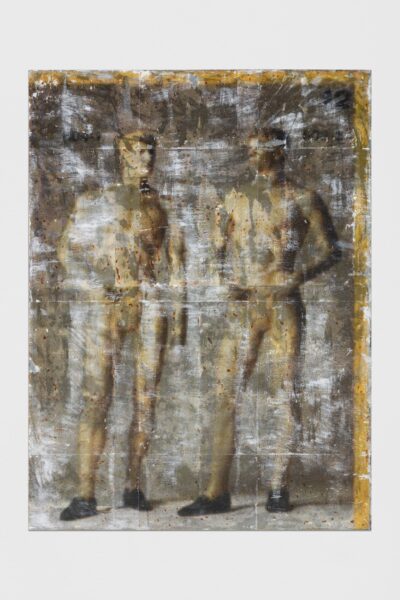

The sign and formal multifacetedness that emerges in the practices of historicized artists such as Accardi and Sheila Hicks in dialogue with the more contemporary languages of James Bantone, Becky Beasley, Pascale Birchler, Azize Ferizi, Simone Holliger, Deborah-Joyce Holman, and PRICE – almost all Millennials like me – goes beyond the purity of the media and inhabits a liminal zone in which the figure, self-representation, volumes, and image are liberated. Uprooted from all sources and locations as they are, Bantone’s corporeal mannequins end up being swallowed by surfaces, by colours and by layers of reflection on the power of the body. In contrast, Birchler’s self-portrait makes us reconfront uncomfortable questions such as self-scrutiny: which forms of identity will stand the test of time? By simulating a monumentality which implodes systematically, Holliger’s volumes find comfort in a fragile and perishable material which is complimentary to Ferizi’s sculptopainted forms. Ferizi finds new impulses towards the artistic object which presents itself directly, without any altering of reality. In contrast, Beasley’s sculptural research rethinks the intimacy of inhabiting space through silent and often muscular objects. Holman returns to his work on signs carefully returning them under the form of identity and historical memory. This is a way to confront the conflict between socially normative categories which in PRICE’s protean practice resolves itself in imposing architecture which ridicules the white cube or in effluvia which work on the absence and the smell of the form.

In this way, those forms which have inspired the exhibition become disconnected from signs, and by opening up to a polymorphism which transcends recognizable geometries and hierarchical criteria, surprisingly connect themselves to the sensitivity of the youngest generations, who willingly make themselves the game of the object, of the form and if its coexistence in space and time.

Eleonora Milani

Untitled 1, 2023glass-sheet, scent diffuser, scent nr. 1

Untitled 1, 2023glass-sheet, scent diffuser, scent nr. 1

35×25×8 cm Untitled 3, 2023glass-sheet, scent diffuser, scent nr. 3

Untitled 3, 2023glass-sheet, scent diffuser, scent nr. 3

35×25×8 cm Untitled 4, 2023glass-sheet, scent diffuser, scent nr. 4

Untitled 4, 2023glass-sheet, scent diffuser, scent nr. 4

35×25×8 cm Thicc and Slippery, 2020Ink on human teeth, wire, aluminium, mirror

Thicc and Slippery, 2020Ink on human teeth, wire, aluminium, mirror

7×7×7 cm Verde e grigio scuro, 2000vinyl paint on raw canvas

Verde e grigio scuro, 2000vinyl paint on raw canvas

120,5×160,7×2,4 cm The Monk, 2023oil on canvas, metallic wire

The Monk, 2023oil on canvas, metallic wire

150×160×160 cmPh. Andrea Rossetti Untitled (L’Air du Temps IIII), 2024polyester fabric, aluminum rails

Untitled (L’Air du Temps IIII), 2024polyester fabric, aluminum rails

dimensions variable

Ph. Andrea Rossetti Untitled (see me?), 2024Acrylic transfer on steel

Untitled (see me?), 2024Acrylic transfer on steel

250×120×10 cm

Ph. James Bantone 604-1 & 603-3 (Umm Hmm), 2024Acrylic transfer on steel

604-1 & 603-3 (Umm Hmm), 2024Acrylic transfer on steel

120×83 cm

Ph. Andrea Rossetti / Hector Chico Commingled compression, 2024Paper, glue, pigment, dammar resin

Commingled compression, 2024Paper, glue, pigment, dammar resin

198×155×50 cm

Ph. Andrea Rossetti Mirror (Silvery), 2012Diasec mounted Lambda print

Mirror (Silvery), 2012Diasec mounted Lambda print

170×50×0,4 cm

Edition of 2 + 1 AP The ovals (Beads & Lashes), 2012Diasec mounted Lambda print

The ovals (Beads & Lashes), 2012Diasec mounted Lambda print

170×50×0,4 cm

Edition of 2 + 1 AP Still Untitled, 2023Wood, gypsum, modeling clay, glaze, pigments

Still Untitled, 2023Wood, gypsum, modeling clay, glaze, pigments

padding, textile, glass pearls, artificial hair, chair

131×120×80 cm

Ph. Andrea Rossetti Still untitled, 2023Wood, acrylic glass, metal mesh,

Still untitled, 2023Wood, acrylic glass, metal mesh,

dried palm leaves, three textile bows76×140×8 cm each

140 x 152 x 8 cm overall dimensions

Ph. Marc Tatti Untitled (sexyy), 2024Acrylic transfer on steel

Untitled (sexyy), 2024Acrylic transfer on steel

125×85 cm

Ph. Andrea Rossetti / Héctor Chico