08/05 - 18/07, 2014

IDEA OF FRACTURE OPINIONE LATINA | 2

Curated by Jacopo Crivelli Visconti

As the collaborator of Oscar Niemeyer on some of the most suggestive projects in Brasília, Athos Bulcão is the creator of the tiles that adorn so many of the public buildings as well as the edifices of the capital’s superquadras. The peculiarity of Bulcão’s method was to leave room for the creativity of the workers installing the tiles, to whom he supplied only some general instructions (usually concerned with avoiding the creation of compositions that would be too “obvious”), leaving them for the most part free to juxtapose the designs how they saw fit. If, over the course of his very long career, Oscar Niemeyer has on more than one occasion affirmed his militant communism (a claim belied, or at least weakened, by his innumerable public commissions realized for various political regimes), Bulcão’s activity reveals authentically and deeply democratic aims. The great mural painting by Laercio Redondo (part of the series Lembranças de Brasília, 2012) pays homage to Bulcão and to his method which is so open and subject to the circumstances life that are beyond one’s control; in this sense he is subtly anti-modernist. Although not directly inspired by Bulcão, the curtains produced by Felipe Mujica for the exhibition, part of a series in progress, should be interpreted in an analogous manner, since the artist defines some fundamental parameters, formally ascribable to the modernist tradition, but then goes on to leave a certain margin of freedom to the collaborators who produce them, by allowing them, for example, to choose the color of the fabrics. The collages and the sculptures by Elena Damiani often take the same repertory of modernist architecture as a starting point, but in this case the purity of the forms appears as contaminated, almost repudiated by the surprisingly fluid juxtaposition of utterly distinct architecture and spaces, in the case of the collages; and by the very widely differing materials such as glass and marble (the one transparent and fragile, the other strong and opaque), in the case of the sculptures. Through the images Damiani moreover establishes, albeit in a fragmentary and non-linear fashion, a narrative; a fantastical and complex universe in which we feel it would be possible to live, and, perhaps, in which someone does indeed live.

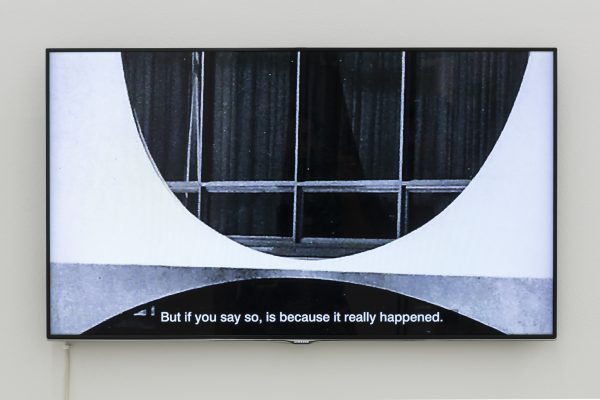

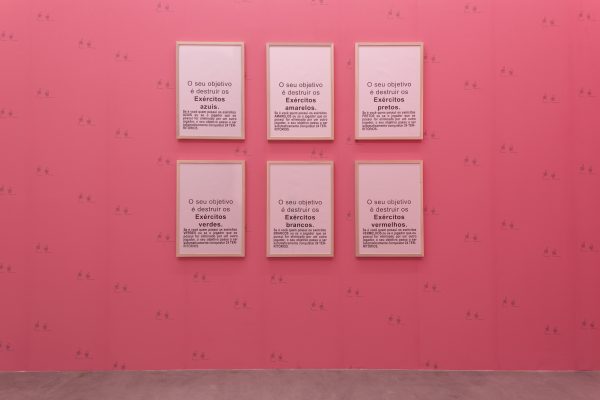

Despite not having a soundtrack, Foro (Armando Andrade Tudela, 2013) is intrinsically musical: the hands of the artist and of the architecture students who have helped him to build a model of the Endless House developed by Friedrich Kiesler have designed a concert of extremely melodic forms and gestures. The synesthetic experience transmitted by the film is coherent with its subject: Kiesler’s utopian house was at the same time an idea and the realization of an idea, fusing in a single artifact two theoretically distinct moments. The sculptures of the series Untitled (2014), produced by Andrade Tudela for this exhibition, use the same material and a principal which is in some way specular, as they do not allude to a hypothetical future construction on a larger scale, of which they would constitute the model, but of the modus operandi according to which they are constructed. The artist prepares the molds for the sculptures so that, when they are removed from the mold, some “linings” break, and join the final form by painstakingly observing the sculpture from every angle to find the exact point in which to insert the broken section. Andrade Tudela has realized two versions for each mold, inevitably different from one another because he cannot control the exact point in which the “lining” will break, and, consequently, where the right place to insert the broken section will be. The idea of a fracture, of a violence often invisible, but which lies beneath the creation of utopian, spectacular and charming architecture, forms in a certain sense the core of the exhibition. The ruthless suppression of workers’ strike during the construction of Brasília, and above all the manner in which this suppression is denied by Oscar Niemeyer and Lucio Costa in the interviews conducted by Clara Ianni in Free Form / Forma Livre, Parte I and II (2013), speak of precisely this fracture that has never-quite-healed on which the capital was built, and by metonymy the country and even the continent itself. An atavistic fracture, which can be traced all the way back to the founding trauma of colonization, and the way in which, in the following centuries, the sociopolitical arena has remained substantially the same, continuously showing the same asymmetric division of power and access to natural resources. The war to which Ianni alludes in War II (2011-12) is only by appearances that of a board game: what makes these ruthless and totalitarian aims suddenly frightening and yet familiar, it not their insertion in a different context, but the manner in which, in this new context, they echo a tragic past, and perhaps an unobserved present. Like architecture, language can both reveal and hide, it can propose military aims, or, more subtly, choose not to speak of the problem directly, but to allude to it transversally, silently.

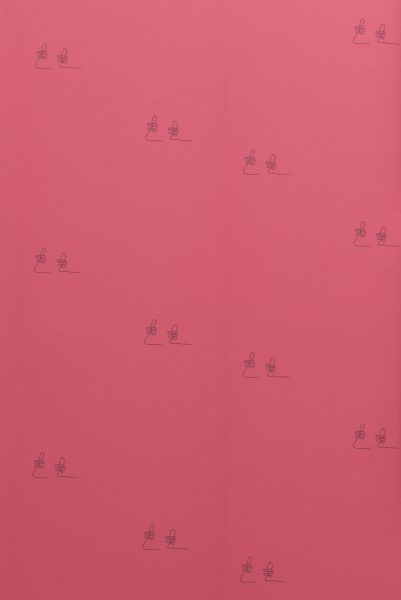

This is what forms Alejandro Cesarco’s Footnotes, 2014, which evoke, in a seemingly unintellectual context, parallel realities, the capacity of art and language to transform reality, revealing its fantastic side. In this sense, even though they may seem like a digression from the exhibition’s main themes, Cesarco’s notes in fact constitute the key to understanding all that can be (and is) said and denied, that language is an architecture of the word, which, by constructing various levels of interpretation, on one hand conceals, almost protectively, the state of things, and on the other allows it to be filtered, sifting out the fracture that is to be sought, once again, beyond what we believe we see. Analogously, the graphic alphabet invented by Mateo López to compose his poetry-sculptures, which allude to the great tradition of concrete poetry in Latin America, is not immediately comprehensible. With his words made of folded sheets of paper, López doesn’t so much say as refer, suggest, and open up a field of possible combinations. Thus the lithograph which provides the key to interpreting the work is a sort of dictionary that should allow one to understand, but it is clear that it does not tell us everything, because that would be impossible: some things, when one attempts to explain them, dissolve into thin air. And it is in this unsayable context, which in certain sense precedes the works, or underlies them, almost to highlight the need to look beyond appearances, that Runo Lagomarsino has installed it wallpaper, transforming the exhibition space into a theatrical stage adorned with a sign that is apparently decorative, but which actually speaks, once again, of violence and colonization. Illiterate, the conquistador Francisco Pizarro would sign is name by twice repeating a sort of abstract scrawl, a sign as arbitrary and personal as any violence, which always had to be authenticated by a public notary who signed in the middle. If, as suggested by the title of another works of Lagomarsino’s, Colombo’s enterprise might seem, at the beginning, like a joke (We All Laughed at Christopher Columbus, 2003), today nobody is laughing; Pizarro’s lopsided signature closes the circle opened by the cordial forms of Athos Bulcão, and reminds us that it remains, indelible and alert, underneath any new attempt to establish an authentically democratic process in Latin America.

Jacopo Crivelli Visconti

As the collaborator of Oscar Niemeyer on some of the most suggestive projects in Brasília, Athos Bulcão is the creator of the tiles that adorn so many of the public buildings as well as the edifices of the capital’s superquadras. The peculiarity of Bulcão’s method was to leave room for the creativity of the workers installing the tiles, to whom he supplied only some general instructions (usually concerned with avoiding the creation of compositions that would be too “obvious”), leaving them for the most part free to juxtapose the designs how they saw fit. If, over the course of his very long career, Oscar Niemeyer has on more than one occasion affirmed his militant communism (a claim belied, or at least weakened, by his innumerable public commissions realized for various political regimes), Bulcão’s activity reveals authentically and deeply democratic aims. The great mural painting by Laercio Redondo (part of the series Lembranças de Brasília, 2012) pays homage to Bulcão and to his method which is so open and subject to the circumstances life that are beyond one’s control; in this sense he is subtly anti-modernist. Although not directly inspired by Bulcão, the curtains produced by Felipe Mujica for the exhibition, part of a series in progress, should be interpreted in an analogous manner, since the artist defines some fundamental parameters, formally ascribable to the modernist tradition, but then goes on to leave a certain margin of freedom to the collaborators who produce them, by allowing them, for example, to choose the color of the fabrics. The collages and the sculptures by Elena Damiani often take the same repertory of modernist architecture as a starting point, but in this case the purity of the forms appears as contaminated, almost repudiated by the surprisingly fluid juxtaposition of utterly distinct architecture and spaces, in the case of the collages; and by the very widely differing materials such as glass and marble (the one transparent and fragile, the other strong and opaque), in the case of the sculptures. Through the images Damiani moreover establishes, albeit in a fragmentary and non-linear fashion, a narrative; a fantastical and complex universe in which we feel it would be possible to live, and, perhaps, in which someone does indeed live.

Despite not having a soundtrack, Foro (Armando Andrade Tudela, 2013) is intrinsically musical: the hands of the artist and of the architecture students who have helped him to build a model of the Endless House developed by Friedrich Kiesler have designed a concert of extremely melodic forms and gestures. The synesthetic experience transmitted by the film is coherent with its subject: Kiesler’s utopian house was at the same time an idea and the realization of an idea, fusing in a single artifact two theoretically distinct moments. The sculptures of the series Untitled (2014), produced by Andrade Tudela for this exhibition, use the same material and a principal which is in some way specular, as they do not allude to a hypothetical future construction on a larger scale, of which they would constitute the model, but of the modus operandi according to which they are constructed. The artist prepares the molds for the sculptures so that, when they are removed from the mold, some “linings” break, and join the final form by painstakingly observing the sculpture from every angle to find the exact point in which to insert the broken section. Andrade Tudela has realized two versions for each mold, inevitably different from one another because he cannot control the exact point in which the “lining” will break, and, consequently, where the right place to insert the broken section will be. The idea of a fracture, of a violence often invisible, but which lies beneath the creation of utopian, spectacular and charming architecture, forms in a certain sense the core of the exhibition. The ruthless suppression of workers’ strike during the construction of Brasília, and above all the manner in which this suppression is denied by Oscar Niemeyer and Lucio Costa in the interviews conducted by Clara Ianni in Free Form / Forma Livre, Parte I and II (2013), speak of precisely this fracture that has never-quite-healed on which the capital was built, and by metonymy the country and even the continent itself. An atavistic fracture, which can be traced all the way back to the founding trauma of colonization, and the way in which, in the following centuries, the sociopolitical arena has remained substantially the same, continuously showing the same asymmetric division of power and access to natural resources. The war to which Ianni alludes in War II (2011-12) is only by appearances that of a board game: what makes these ruthless and totalitarian aims suddenly frightening and yet familiar, it not their insertion in a different context, but the manner in which, in this new context, they echo a tragic past, and perhaps an unobserved present. Like architecture, language can both reveal and hide, it can propose military aims, or, more subtly, choose not to speak of the problem directly, but to allude to it transversally, silently.

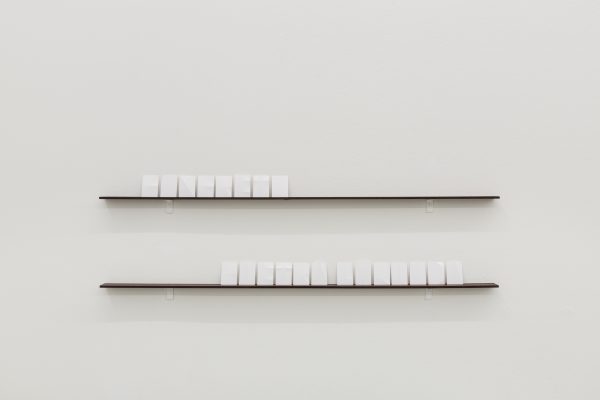

This is what forms Alejandro Cesarco’s Footnotes, 2014, which evoke, in a seemingly unintellectual context, parallel realities, the capacity of art and language to transform reality, revealing its fantastic side. In this sense, even though they may seem like a digression from the exhibition’s main themes, Cesarco’s notes in fact constitute the key to understanding all that can be (and is) said and denied, that language is an architecture of the word, which, by constructing various levels of interpretation, on one hand conceals, almost protectively, the state of things, and on the other allows it to be filtered, sifting out the fracture that is to be sought, once again, beyond what we believe we see. Analogously, the graphic alphabet invented by Mateo López to compose his poetry-sculptures, which allude to the great tradition of concrete poetry in Latin America, is not immediately comprehensible. With his words made of folded sheets of paper, López doesn’t so much say as refer, suggest, and open up a field of possible combinations. Thus the lithograph which provides the key to interpreting the work is a sort of dictionary that should allow one to understand, but it is clear that it does not tell us everything, because that would be impossible: some things, when one attempts to explain them, dissolve into thin air. And it is in this unsayable context, which in certain sense precedes the works, or underlies them, almost to highlight the need to look beyond appearances, that Runo Lagomarsino has installed it wallpaper, transforming the exhibition space into a theatrical stage adorned with a sign that is apparently decorative, but which actually speaks, once again, of violence and colonization. Illiterate, the conquistador Francisco Pizarro would sign is name by twice repeating a sort of abstract scrawl, a sign as arbitrary and personal as any violence, which always had to be authenticated by a public notary who signed in the middle. If, as suggested by the title of another works of Lagomarsino’s, Colombo’s enterprise might seem, at the beginning, like a joke (We All Laughed at Christopher Columbus, 2003), today nobody is laughing; Pizarro’s lopsided signature closes the circle opened by the cordial forms of Athos Bulcão, and reminds us that it remains, indelible and alert, underneath any new attempt to establish an authentically democratic process in Latin America.

Jacopo Crivelli Visconti

Restauro (Restoration), 2012

Restauro (Restoration), 2012

charcoal stencil, water, ferns

dimensions variable Untitled / Diagonal (Curtain 2), 2014

Untitled / Diagonal (Curtain 2), 2014

fabric and thread

274×156 cm Footnote #13, 2014vinyl text on wall

Footnote #13, 2014vinyl text on wall

dimensions variable Foro, 2013

Foro, 2013

16 mm film transferred to digital

10' 53" Macelos n°4, 2014marble, glass,photo

Macelos n°4, 2014marble, glass,photo

70×25×60 cm Placements II, 2014print on found bookplate

Placements II, 2014print on found bookplate

52×62 cm Placements I, 2014print on found bookplate

Placements I, 2014print on found bookplate

52×62 cm Untitled from the series Lembranca de Brasilia (Memory of Brasilia), 2012

Untitled from the series Lembranca de Brasilia (Memory of Brasilia), 2012

silkscreen and acrylic paint on plywood

100×140 cm Untitled (Milan) 3, 2014

Untitled (Milan) 3, 2014

plaster

41×37×20 cm Footnote #14, 2014vinyl text on wall

Footnote #14, 2014vinyl text on wall

dimensions variable Forma Livre (Brasilia), 20132 channel video installation, sound

Forma Livre (Brasilia), 20132 channel video installation, sound

6'24" (video 1: 2'59", video 2: 4'18") Paper Poems, 20112 wooden shelves and papers

Paper Poems, 20112 wooden shelves and papers

90×3,5 cm each War II, 2010

War II, 2010

silkscreen on Fabriano 90g paper

63×43 cm

each (6 parts) We all laughed at Christopher Columbus, 2003single slideprojection on MDF

We all laughed at Christopher Columbus, 2003single slideprojection on MDF

45,5 ×25,5×42,5 cm As in Pizarro, 2010wallpaper

As in Pizarro, 2010wallpaper

dimensions variable Mateo López

Mateo López

litografia

52×72 cm Untitled / Diagonal (Curtain 1), 2014

Untitled / Diagonal (Curtain 1), 2014

fabric and thread

274×167 cm Untitled, 2014

Untitled, 2014

plaster

34×23×42 cm