Opening 19/09 - 19/09 - 09/11, 2013

-

Matthias Bitzer

Amherst/Ether/Fields

Do we think of space as a Euclidean “container space”: static, homogenous and measurable, like we were taught in geometry class? Or is space a “place, with which one can do something”, which, like a word, expresses a change, a moment in time subject to volatility like in what Michel de Certeau calls “the discourse of echoing steps”?

Starting from the second half of the 19th century concepts have been developed that put emphasis on the relationality of space and its dependence on the human body and on the various interactions between time and space.

In this way space develops only inside a dialogue process and manifests itself foremost in a vision relating to the subject. Space is closely intertwined with time. Georges Perec (1974) writes of a significant difference between the two:

“Space seems either more tamed, or more inoffensive than time: everywhere one goes one meets people with a watch, and only very seldom people with a compass. We always need to know what time it is (and how many of us still know how to deduce it from the position of the sun?) but we never ask ourselves where we are. We believe we know: we are at home, at the office, on the metro, in the street.”

Though this distinction of Perec’s may seem to have lost its relevance in the era of smartphones and Google Maps, the use of these portable navigational tools is not automatically accompanied by a greater awareness of space. The real and daily surroundings are represented cartographically down to the minutest of details, but the intimate mental space of each individual still eludes this process of controlled mapping.

In his third personal show at Francesca Minini, Matthias Bitzer is exhibiting new works in which the Berlin artist has taken these notions as a point of departure. The title Amherst/Ether/Fields refers to the birth and death of the American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886). Dickinson spent her entire life in Amherst, a town in western Massachusetts, isolated like a hermit. The poet’s only window to the outside world was her letters, in which imagination prevails over real experiences; hers is a voyage of building the world through fancy. She flies with her mind, as Bitzer himself says: “My mind is moving but my body lies still”.

‘Ether’ comes from Greek and originally meant “burning, radiant, shining”; and in a figurative sense the vast cloudless heavens, a living and refined primordial substance, the soul of the world. The “Fields” of the title recall the landscape that extends out into the distance up to the horizon and evoke the fusion of man with the space that surrounds him.

Real and imaginary space move, mix, and cross over from one into the other. The subject finds itself as though dissolved into the center of a liquid identity.

Matthias Bitzer expresses this concept in his painting installation Leimakides (my mind is moving but my body lies still). The painting on the left depicts a female drawn in profile, who is looking out of a window to observe, alone and undisturbed, all of the tiniest details of the external world, like Emily Dickinson did from her study. The window with its partitions serves as opening to the outside, but at the same time delimits the eye’s visual space. The next works show various levels of definition, from a delicate and fragmented kaleidoscopic collage on an ephemeral structure of smoke rings, to vivid spots of color that gradually develop into the spectrum of grays.

A characteristic of Matthias Bitzer’s work is the resolution of the figurative in ornamental geometries, the overlapping of divergent images, and the use of a vocabulary of abstract forms that through a changing perspective always place emphasis on figurative details.

A whiteout, as a weather phenomenon, makes spatial boundaries disappear, the edges of sky and land begin to waver. This phenomenon takes place in a snow-clad landscape in particularly intense sunlight, mainly in polar regions and in the mountains, and often leads to disorientation and vertigo. One has the feeling of being in a gray space that is empty and infinite, an effect that the artist recreates in the second room of the gallery by eliminating corners and boundaries and thus denying the clarity (acuity) of the architectural form.

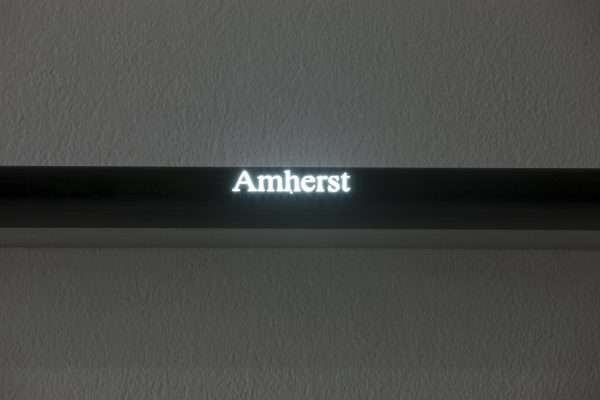

The only orienting elements are the design on the wall and three neon lights lacquered black, on which we can read the exhibition’s title.

The linearity of time seems to have been suspended in favor of a cycle (Nymoh/Noir/Nothingness), which blots out the room (Time itself comes in drops). In this way the perception of familiar places changes continuously, and inside and outside alternate, inverting themselves repeatedly.

“[…] and you have felt the horizon hav’nt you – and did the sea – never come so close as to make you dance?”

Do we think of space as a Euclidean “container space”: static, homogenous and measurable, like we were taught in geometry class? Or is space a “place, with which one can do something”, which, like a word, expresses a change, a moment in time subject to volatility like in what Michel de Certeau calls “the discourse of echoing steps”?

Starting from the second half of the 19th century concepts have been developed that put emphasis on the relationality of space and its dependence on the human body and on the various interactions between time and space.

In this way space develops only inside a dialogue process and manifests itself foremost in a vision relating to the subject. Space is closely intertwined with time. Georges Perec (1974) writes of a significant difference between the two:

“Space seems either more tamed, or more inoffensive than time: everywhere one goes one meets people with a watch, and only very seldom people with a compass. We always need to know what time it is (and how many of us still know how to deduce it from the position of the sun?) but we never ask ourselves where we are. We believe we know: we are at home, at the office, on the metro, in the street.”

Though this distinction of Perec’s may seem to have lost its relevance in the era of smartphones and Google Maps, the use of these portable navigational tools is not automatically accompanied by a greater awareness of space. The real and daily surroundings are represented cartographically down to the minutest of details, but the intimate mental space of each individual still eludes this process of controlled mapping.

In his third personal show at Francesca Minini, Matthias Bitzer is exhibiting new works in which the Berlin artist has taken these notions as a point of departure. The title Amherst/Ether/Fields refers to the birth and death of the American poet Emily Dickinson (1830-1886). Dickinson spent her entire life in Amherst, a town in western Massachusetts, isolated like a hermit. The poet’s only window to the outside world was her letters, in which imagination prevails over real experiences; hers is a voyage of building the world through fancy. She flies with her mind, as Bitzer himself says: “My mind is moving but my body lies still”.

‘Ether’ comes from Greek and originally meant “burning, radiant, shining”; and in a figurative sense the vast cloudless heavens, a living and refined primordial substance, the soul of the world. The “Fields” of the title recall the landscape that extends out into the distance up to the horizon and evoke the fusion of man with the space that surrounds him.

Real and imaginary space move, mix, and cross over from one into the other. The subject finds itself as though dissolved into the center of a liquid identity.

Matthias Bitzer expresses this concept in his painting installation Leimakides (my mind is moving but my body lies still). The painting on the left depicts a female drawn in profile, who is looking out of a window to observe, alone and undisturbed, all of the tiniest details of the external world, like Emily Dickinson did from her study. The window with its partitions serves as opening to the outside, but at the same time delimits the eye’s visual space. The next works show various levels of definition, from a delicate and fragmented kaleidoscopic collage on an ephemeral structure of smoke rings, to vivid spots of color that gradually develop into the spectrum of grays.

A characteristic of Matthias Bitzer’s work is the resolution of the figurative in ornamental geometries, the overlapping of divergent images, and the use of a vocabulary of abstract forms that through a changing perspective always place emphasis on figurative details.

A whiteout, as a weather phenomenon, makes spatial boundaries disappear, the edges of sky and land begin to waver. This phenomenon takes place in a snow-clad landscape in particularly intense sunlight, mainly in polar regions and in the mountains, and often leads to disorientation and vertigo. One has the feeling of being in a gray space that is empty and infinite, an effect that the artist recreates in the second room of the gallery by eliminating corners and boundaries and thus denying the clarity (acuity) of the architectural form.

The only orienting elements are the design on the wall and three neon lights lacquered black, on which we can read the exhibition’s title.

The linearity of time seems to have been suspended in favor of a cycle (Nymoh/Noir/Nothingness), which blots out the room (Time itself comes in drops). In this way the perception of familiar places changes continuously, and inside and outside alternate, inverting themselves repeatedly.

“[…] and you have felt the horizon hav’nt you – and did the sea – never come so close as to make you dance?”

Untitled, 2013walldrawing, poem

Untitled, 2013walldrawing, poem

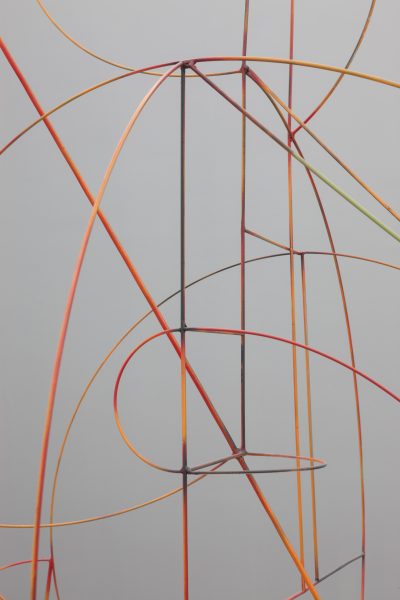

dimensions variable Inmost Iconoclasm, 2013metal, wood, spray paint

Inmost Iconoclasm, 2013metal, wood, spray paint

199×110×127 cm Inmost Iconoclasm, 2013, detailmetal, wood, spray paint

Inmost Iconoclasm, 2013, detailmetal, wood, spray paint

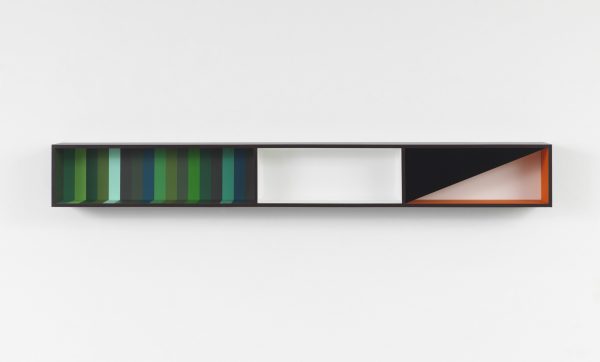

199×110×127 cm Amherst/ Ether/ Fields, 2013paint on wood, mirror, glass

Amherst/ Ether/ Fields, 2013paint on wood, mirror, glass

20×160×15 cm Leimakides (my mind is moving but my body lies still), 2013acrylic and ink on canvas, glass, wood, acrylic glass, neon tubes, paper

Leimakides (my mind is moving but my body lies still), 2013acrylic and ink on canvas, glass, wood, acrylic glass, neon tubes, paper

120×100 cm

each, six parts Nymph/Noir/Nothingness, 2013mixed media

Nymph/Noir/Nothingness, 2013mixed media

200 cm diameter Emily, 2013acrylic and ink on canvas

Emily, 2013acrylic and ink on canvas

140×120 cm Time Itself Comes in Drops, 2013wood, lacquer, neon tubes

Time Itself Comes in Drops, 2013wood, lacquer, neon tubes

dimensions variable Time Itself Comes in Drops, 2013, detailwood, lacquer, neon tubes

Time Itself Comes in Drops, 2013, detailwood, lacquer, neon tubes

dimensions variable Time Itself Comes in Drops, 2013, detailwood, lacquer, neon tubes

Time Itself Comes in Drops, 2013, detailwood, lacquer, neon tubes

dimensions variable Untitled, 2013pencil and pencil on paper, wood, glass

Untitled, 2013pencil and pencil on paper, wood, glass

100×70 cm Amherst/Ether/Fields, 2013neons, metal

Amherst/Ether/Fields, 2013neons, metal

length 360 cm Amherst/Ether/Fields, 2013, detailneons, metal

Amherst/Ether/Fields, 2013, detailneons, metal

length 360 cm Amherst/Ether/Fields, 2013, detailneons, metal

Amherst/Ether/Fields, 2013, detailneons, metal

length 360 cm Amherst/Ether/Fields, 2013, detailneons, metal

Amherst/Ether/Fields, 2013, detailneons, metal

length 360 cm Phosphor Notes (Hypomnema), 2013mixed media

Phosphor Notes (Hypomnema), 2013mixed media

40 ×30 cm each (nine parts)