Opening 26/09 - 22/09 - 27/11, 2020

-

Matthias Bitzer

A little image-shrine for the roadside

That “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” has by now become a platitude. It declares that the perception of beauty is utterly subjective. Yet one thing about beauty that everyone can probably agree on is that it provokes some reaction in anyone who comes in contact with it, whether enchantment, pleasure, fascination, or serenity. While beauty can be observed in nature this short outline of thoughts concerns itself instead with beauty created by humans, and specifically the aesthetic experience of art.

Is it possible to consider beauty objectively in the realm of art? To imagine that beauty exists in its own right, within something such as a painting, a sculpture, or a photograph, autonomously from a person’s experience of the work? This understanding of beauty goes back to Plato, who expressed the idea that beauty does indeed exist purely in the appearance and structure of art, outside of any observer’s perception. Another thought on beauty, one that also argues that beauty can be qualified objectively, comes from Aristotle, whose view of beauty in art was guided by formal characteristics such as proportion, symmetry, balance, or order. Both of these concepts of beauty stand in opposition to the belief that beauty is in the viewer’s mind and a matter of personal taste.

Another support for an objective approach to understanding beauty is the inherent paradox of subjective judgments of beauty. If it is true that an emotional process of the mind defines beauty, then one could argue that beauty is essentially meaningless, as it is merely a matter of individual preference. Subjective conclusions about what is beautiful and what is not lead down a dangerous path in which personal feelings and preferences obstruct and overwhelm a possible universal agreement on beauty.

This leads us to another platitude we so often hear from museum visitors: “Is this art?” A postmodern perspective that has for many decades dominated our judgment of art can be summed up in the rather banal and trite idea of anything goes. If everything and anything can be art, then art defies any definition.

Given the enormous amounts of art made, exhibited, and sold, it seems only appropriate to look for something more concrete than an anything-goes attitude and seek to identify particular characteristics and criteria that will allow us to think about art in universal terms. Yet we should also not forget that conventions in the art world apply to what we consider art. A group of alleged experts—art historians, art critics, and curators—determine what art we should look at and what is a waste of our time and energy. In the art world, for a work of art to be recognized as such, it has to fulfill two specific qualities: it has to affirm the art made in the past and simultaneously deviate from it to signal some change, novelty, or progress worth considering.

In light of the above, let us turn to the question of how to judge art. Some might argue that a work of art should be judged without influence from a personal or emotional perspective. Yet this personal haze is all too often present when people approach art, and is conveyed in expressions such as “it speaks to me” or “I know what I like.”

As with beauty, to appreciate art fully, we might need to view it in its own right, and not for any particular purpose. We must develop an aesthetic attitude that is based not on feeling beauty but on thinking beauty. This, above all, will not only help us understand and experience beauty and art in a more involved and complex manner but also allow us to consider art’s place in this world differently.

That “beauty is in the eye of the beholder” has by now become a platitude. It declares that the perception of beauty is utterly subjective. Yet one thing about beauty that everyone can probably agree on is that it provokes some reaction in anyone who comes in contact with it, whether enchantment, pleasure, fascination, or serenity. While beauty can be observed in nature this short outline of thoughts concerns itself instead with beauty created by humans, and specifically the aesthetic experience of art.

Is it possible to consider beauty objectively in the realm of art? To imagine that beauty exists in its own right, within something such as a painting, a sculpture, or a photograph, autonomously from a person’s experience of the work? This understanding of beauty goes back to Plato, who expressed the idea that beauty does indeed exist purely in the appearance and structure of art, outside of any observer’s perception. Another thought on beauty, one that also argues that beauty can be qualified objectively, comes from Aristotle, whose view of beauty in art was guided by formal characteristics such as proportion, symmetry, balance, or order. Both of these concepts of beauty stand in opposition to the belief that beauty is in the viewer’s mind and a matter of personal taste.

Another support for an objective approach to understanding beauty is the inherent paradox of subjective judgments of beauty. If it is true that an emotional process of the mind defines beauty, then one could argue that beauty is essentially meaningless, as it is merely a matter of individual preference. Subjective conclusions about what is beautiful and what is not lead down a dangerous path in which personal feelings and preferences obstruct and overwhelm a possible universal agreement on beauty.

This leads us to another platitude we so often hear from museum visitors: “Is this art?” A postmodern perspective that has for many decades dominated our judgment of art can be summed up in the rather banal and trite idea of anything goes. If everything and anything can be art, then art defies any definition.

Given the enormous amounts of art made, exhibited, and sold, it seems only appropriate to look for something more concrete than an anything-goes attitude and seek to identify particular characteristics and criteria that will allow us to think about art in universal terms. Yet we should also not forget that conventions in the art world apply to what we consider art. A group of alleged experts—art historians, art critics, and curators—determine what art we should look at and what is a waste of our time and energy. In the art world, for a work of art to be recognized as such, it has to fulfill two specific qualities: it has to affirm the art made in the past and simultaneously deviate from it to signal some change, novelty, or progress worth considering.

In light of the above, let us turn to the question of how to judge art. Some might argue that a work of art should be judged without influence from a personal or emotional perspective. Yet this personal haze is all too often present when people approach art, and is conveyed in expressions such as “it speaks to me” or “I know what I like.”

As with beauty, to appreciate art fully, we might need to view it in its own right, and not for any particular purpose. We must develop an aesthetic attitude that is based not on feeling beauty but on thinking beauty. This, above all, will not only help us understand and experience beauty and art in a more involved and complex manner but also allow us to consider art’s place in this world differently.

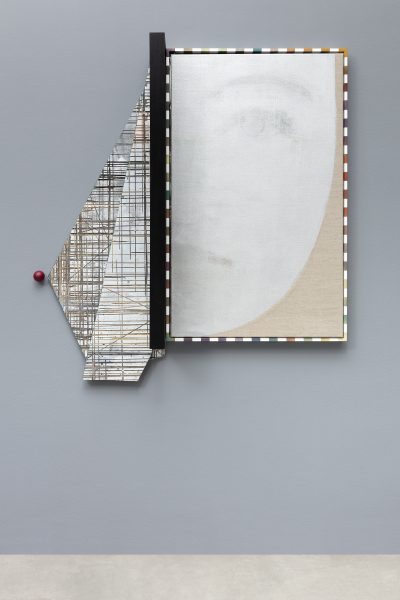

A little image-shrine for the roadside, 2019mixed media

A little image-shrine for the roadside, 2019mixed media

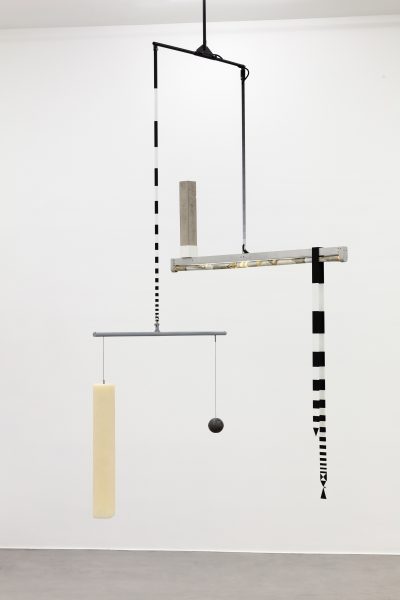

150×100×34 cm Dilemma of relativity, 2018mixed media

Dilemma of relativity, 2018mixed media

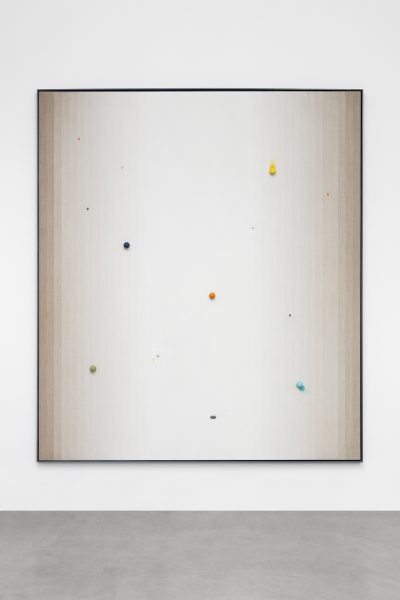

286×150×150 cm La promenade des atomes, 2020acrylic on canvas

La promenade des atomes, 2020acrylic on canvas

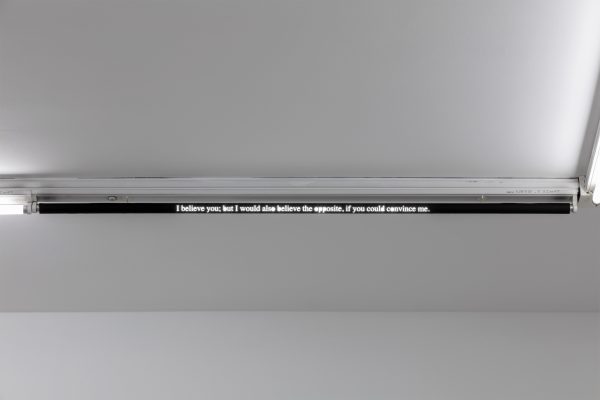

243×210×5 cm I believe you; but I would also believe the opposite if you could convince me, 2020Neon, pvc tubes with adhesive foil

I believe you; but I would also believe the opposite if you could convince me, 2020Neon, pvc tubes with adhesive foil

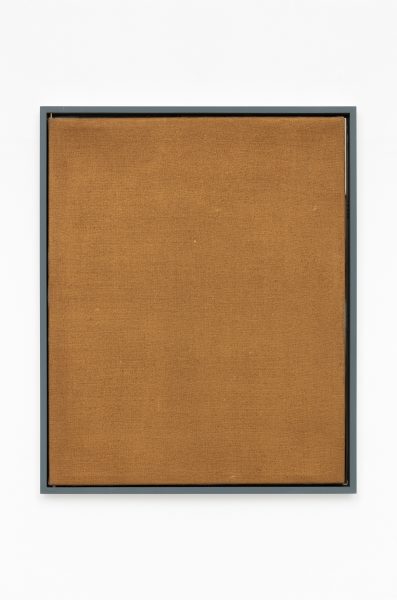

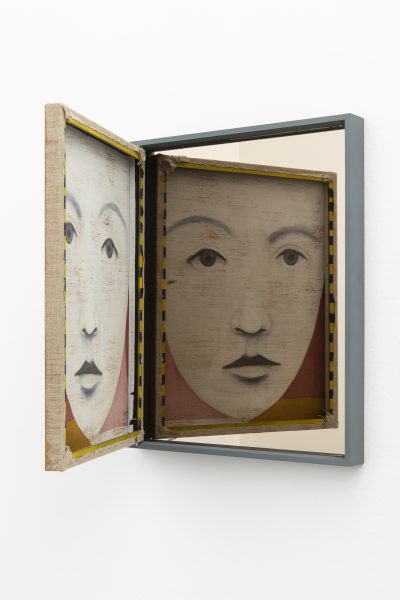

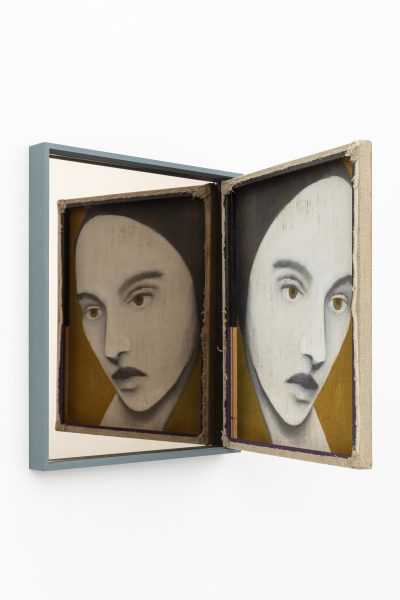

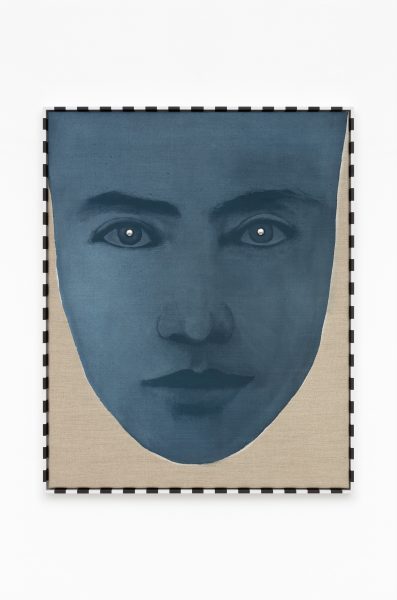

150 cm Icons, 2020acrylic on canvas, mirror

Icons, 2020acrylic on canvas, mirror

55×46×5 cm Icons, 2020acrylic on canvas, mirror

Icons, 2020acrylic on canvas, mirror

55×46×5 cm Icons, 2020acrylic on canvas, mirror

Icons, 2020acrylic on canvas, mirror

55×46×5 cm Icons, 2020acrylic on canvas, mirror

Icons, 2020acrylic on canvas, mirror

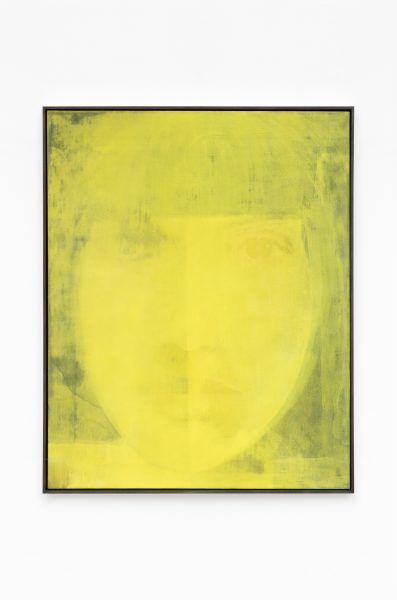

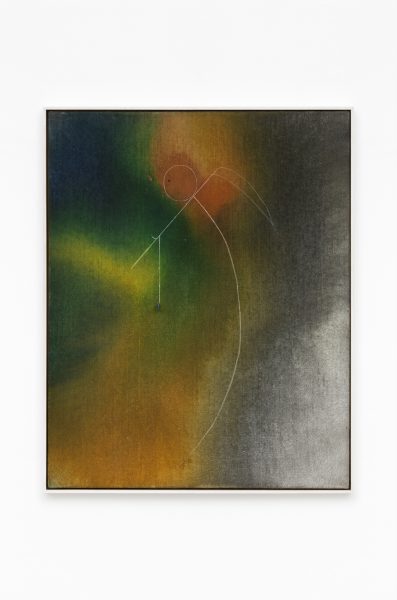

55×46×5 cm La colère (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

La colère (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

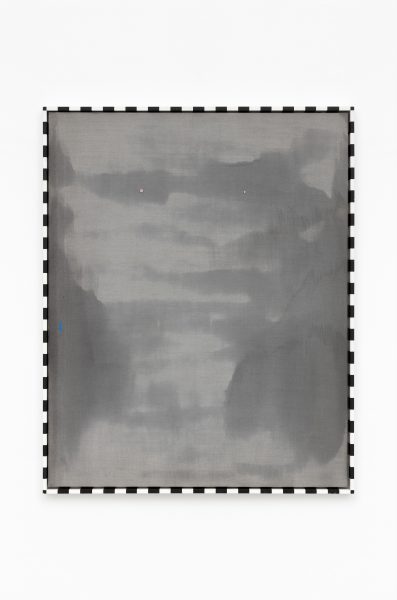

102×83×5 cm The creation of a storm (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

The creation of a storm (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

103×83×5 cm The last laugh (Six Months), 2020acrylic on board

The last laugh (Six Months), 2020acrylic on board

103×82×7 cm Evil Panda (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

Evil Panda (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

103×83×5 cm The dilemma of distribution (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

The dilemma of distribution (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

103×84×6 cm Friendly earthling (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

Friendly earthling (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

103×83×5 cm The collector (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

The collector (Six Months), 2020acrylic on canvas

103×83×5 cm Nova Povera, 2020acrylic on canvas, mirror, wood

Nova Povera, 2020acrylic on canvas, mirror, wood

117,5×112×5 cm All that you call world is the shadow of that substance which you are, 2020Neon, pvc tubes with adhesive foil

All that you call world is the shadow of that substance which you are, 2020Neon, pvc tubes with adhesive foil

150 cm Emily’s window (opens to both sides), 2020mixed media

Emily’s window (opens to both sides), 2020mixed media

42×238×34 cm