27/01 - 11/03, 2023

-

Flavio Favelli

Progetto per fontana e altre figure

A conversation by Flavio Favelli and Francesco Stocchi

Le opere fuori

FF: There is definitely a correspondence between your writing for a newspaper that is not about art and my working with art in a public space, the fact of trying to get out from the museum, from the space that has been assigned to art. For over twenty years I’ve been trying to create projects and works outside of this space and I’ve come to understand very well the deep disinterest, even irritation, combined with the terror, that there is about free thinking, even more that about art. Today’s art puts power and politics in difficulty.

Everything needs to have an explanation, a final purpose, a meaning that’s easy to understand, everything needs to be simple and obvious. But what does trying to “get out” and go “outside” mean? Beyond civic engagement, is there anything else? And this engagement (I agree with Walter Siti and his Against Engagement) should not be understood as an idea of how to “change things for the better”, but simply to change one’s point of view, without any more specific purpose.

So I wouldn’t talk about engagement exactly, but rather of putting “a spanner in the works”.

FS: Engagement as I understand it is an expression of activists, i.e. those who espouse an art about politics that is distinct from political art – an intrinsic, foundational aspect of making art. I read this as putting a spanner in the works, offering up another side of things, and perhaps moving away from the tyranny of good feelings that seems to have taken over art in the last generation. As long as the market aims to attract so much attention of various kinds, free thinking will be left on the side-lines, unless one wants be anti-system at all costs, which is the other side of the coin. There are artists who take on this role, but for obvious reasons there cannot be many of them, as with court jesters who were the only ones who could offend the king without having their head cut off. Presenting your work in a public space is a bit like writing in non-specialist newspaper, such as ll Foglio in my case. The viewer or reader finds content without having to go look for it. Therein lies the difference and the translation work which we are responsible for.

FF: Your mention of “good feelings” brings to mind an insightful article by Mario Perniola, Why Art Must Remain without God, from 2013. Recently, there has been this push from many quarters to cloak art with both the sacred and with a positive and therefore “just” spirit, thereby confirming the view held by the political class and much of society, which has always seen “modern art” as a nuisance. Art is no longer art, it must have a justification, to be used for urban regeneration or the enhancement of the territory; any project in the public sphere, in a time of “royal populism”, must submit to this new law that has seduced artists and administrators: everyone must be made happy. In the public space you cannot conceive of a free and articulated project; artists are called only to resolve situations, for commissions or to celebrate national heroes. It seems that there is a general fear to walk alone, there is a need for consensus, popularity, political correctness and blessings.

FS: “We have art in order to not die of truth”, Nietzsche wrote in 1888, perhaps from Turin. It seems that today it is precisely the other way around, suffocated as we are by a ponderous realism that confuses topicality with contemporaneity. Thus art is promoted by demanding answers, reassurances or confirmation, precisely where questions should arise, because it is by asking questions – and questioning ourselves – that culture thrives. Until the most recent generation, it seems to me that museum directors were much freer to operate compared to today, providing art and the cultural institutions that promote it with a critical role to play in society. Control has gotten progressively greater, resulting in the current situation. Undesirable but inevitable effects of the golden age (from the standpoint of the market and of visibility) that we’ve been experience for about a generation.

FF: Yes, for sure, it seems like an underdiscussed point, but it looks to me as though we are moving towards even more control. Few have realized that a general creativity that is dominated by street art and activism is censoring and suffocating free art. Politics only permits participative projects in line with its ideas, companies only support ecological and sustainable-themed projects. Years ago I went to a party of a Moroccan acquaintance of mine. We were of course all men and after our meal a discussion which began timidly soon heated up. The question was a simple one: despite having emigrated to Italy to find work, despite acknowledging, albeit half-heartedly, their country’s authoritarian regime, the conflict with the West was immediately clear. I saw right away the effects of an authoritarian, ideological and Muslim education (all the participants defined themselves as being very religious). I thought my task was to try to make them understand, in just one afternoon, over tea so sweetened as to be undrinkable, that there was not just one single model of the West, and that one figure, certainly a minoritarian one but no less important for that, was the “contrarian”, to use a term I learned from Franco La Cecla, referring to certain customs of some American warrior tribes. The “contrarian”, or artist as I would say, is someone who, by not doing things in the right way, the right way as defined by society that is, sets the boundaries of the rules and shows that they can be transgressed. This figure’s role is fundamental, in order, as you say, to “not die of truth”. It may be odd to use as an example an experience with fundamentalist Muslims to illustrate today’s situation of political power over art, but if the shoe fits…

FS: “Art is magic freed from the lie of being truth” Adorno said, in explicit contrast to the influence of the political dimension on art. Now it seems that in schools they want to teach the artist to become a reporter of the “truth”, to justify his or her choices socially and set aside the magical aspect. It also happens with films and some literature. The “crises” which occur from time to time throughout the history of art serve to muddle up the boundaries of the rules when they have become too rigid.

A conversation by Flavio Favelli and Francesco Stocchi

Le opere fuori

FF: There is definitely a correspondence between your writing for a newspaper that is not about art and my working with art in a public space, the fact of trying to get out from the museum, from the space that has been assigned to art. For over twenty years I’ve been trying to create projects and works outside of this space and I’ve come to understand very well the deep disinterest, even irritation, combined with the terror, that there is about free thinking, even more that about art. Today’s art puts power and politics in difficulty.

Everything needs to have an explanation, a final purpose, a meaning that’s easy to understand, everything needs to be simple and obvious. But what does trying to “get out” and go “outside” mean? Beyond civic engagement, is there anything else? And this engagement (I agree with Walter Siti and his Against Engagement) should not be understood as an idea of how to “change things for the better”, but simply to change one’s point of view, without any more specific purpose.

So I wouldn’t talk about engagement exactly, but rather of putting “a spanner in the works”.

FS: Engagement as I understand it is an expression of activists, i.e. those who espouse an art about politics that is distinct from political art – an intrinsic, foundational aspect of making art. I read this as putting a spanner in the works, offering up another side of things, and perhaps moving away from the tyranny of good feelings that seems to have taken over art in the last generation. As long as the market aims to attract so much attention of various kinds, free thinking will be left on the side-lines, unless one wants be anti-system at all costs, which is the other side of the coin. There are artists who take on this role, but for obvious reasons there cannot be many of them, as with court jesters who were the only ones who could offend the king without having their head cut off. Presenting your work in a public space is a bit like writing in non-specialist newspaper, such as ll Foglio in my case. The viewer or reader finds content without having to go look for it. Therein lies the difference and the translation work which we are responsible for.

FF: Your mention of “good feelings” brings to mind an insightful article by Mario Perniola, Why Art Must Remain without God, from 2013. Recently, there has been this push from many quarters to cloak art with both the sacred and with a positive and therefore “just” spirit, thereby confirming the view held by the political class and much of society, which has always seen “modern art” as a nuisance. Art is no longer art, it must have a justification, to be used for urban regeneration or the enhancement of the territory; any project in the public sphere, in a time of “royal populism”, must submit to this new law that has seduced artists and administrators: everyone must be made happy. In the public space you cannot conceive of a free and articulated project; artists are called only to resolve situations, for commissions or to celebrate national heroes. It seems that there is a general fear to walk alone, there is a need for consensus, popularity, political correctness and blessings.

FS: “We have art in order to not die of truth”, Nietzsche wrote in 1888, perhaps from Turin. It seems that today it is precisely the other way around, suffocated as we are by a ponderous realism that confuses topicality with contemporaneity. Thus art is promoted by demanding answers, reassurances or confirmation, precisely where questions should arise, because it is by asking questions – and questioning ourselves – that culture thrives. Until the most recent generation, it seems to me that museum directors were much freer to operate compared to today, providing art and the cultural institutions that promote it with a critical role to play in society. Control has gotten progressively greater, resulting in the current situation. Undesirable but inevitable effects of the golden age (from the standpoint of the market and of visibility) that we’ve been experience for about a generation.

FF: Yes, for sure, it seems like an underdiscussed point, but it looks to me as though we are moving towards even more control. Few have realized that a general creativity that is dominated by street art and activism is censoring and suffocating free art. Politics only permits participative projects in line with its ideas, companies only support ecological and sustainable-themed projects. Years ago I went to a party of a Moroccan acquaintance of mine. We were of course all men and after our meal a discussion which began timidly soon heated up. The question was a simple one: despite having emigrated to Italy to find work, despite acknowledging, albeit half-heartedly, their country’s authoritarian regime, the conflict with the West was immediately clear. I saw right away the effects of an authoritarian, ideological and Muslim education (all the participants defined themselves as being very religious). I thought my task was to try to make them understand, in just one afternoon, over tea so sweetened as to be undrinkable, that there was not just one single model of the West, and that one figure, certainly a minoritarian one but no less important for that, was the “contrarian”, to use a term I learned from Franco La Cecla, referring to certain customs of some American warrior tribes. The “contrarian”, or artist as I would say, is someone who, by not doing things in the right way, the right way as defined by society that is, sets the boundaries of the rules and shows that they can be transgressed. This figure’s role is fundamental, in order, as you say, to “not die of truth”. It may be odd to use as an example an experience with fundamentalist Muslims to illustrate today’s situation of political power over art, but if the shoe fits…

FS: “Art is magic freed from the lie of being truth” Adorno said, in explicit contrast to the influence of the political dimension on art. Now it seems that in schools they want to teach the artist to become a reporter of the “truth”, to justify his or her choices socially and set aside the magical aspect. It also happens with films and some literature. The “crises” which occur from time to time throughout the history of art serve to muddle up the boundaries of the rules when they have become too rigid.

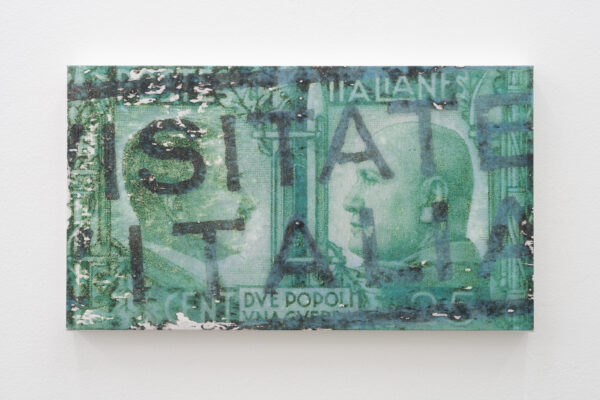

Visitate l’Italia, 2023Transfer gel print on canvas

Visitate l’Italia, 2023Transfer gel print on canvas

39×69,5 cm Progetto per Fontana, 2023assemblage plastic boxes and cans

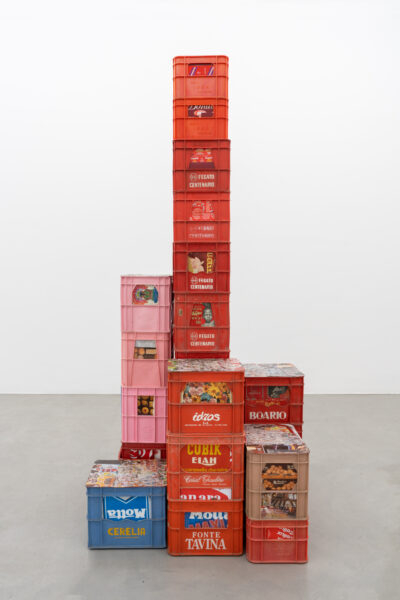

Progetto per Fontana, 2023assemblage plastic boxes and cans

258×123,5×123,5 cm Estate 69, 2023Scratched mirrors on board

Estate 69, 2023Scratched mirrors on board

94×120×5 cm Estate 67, 2023Scratched mirrors on board

Estate 67, 2023Scratched mirrors on board

114×129×5 cm Estate 68, 2023Scratched mirrors on board

Estate 68, 2023Scratched mirrors on board

103,5×123,5×5,5 cm Serie Diplomatica , 2023collage of golden plastic trays on board with frame

Serie Diplomatica , 2023collage of golden plastic trays on board with frame

100×86 cm Riflessi d’argento , 2023collage of praline wrappers on board with frame

Riflessi d’argento , 2023collage of praline wrappers on board with frame

83,5×70 cm Visitate Monterchi, 2022collage of can on road sign

Visitate Monterchi, 2022collage of can on road sign

60,5×90,5 cm Violet Murano, 2022assemblage of chandeliers, light bulbs and neon

Violet Murano, 2022assemblage of chandeliers, light bulbs and neon

105×120×110 cm Estate 83, 2021Scratched mirrors with frame

Estate 83, 2021Scratched mirrors with frame

53×45,5 cm Miele Murano, 2022assemblage of chandeliers, light bulbs and neon

Miele Murano, 2022assemblage of chandeliers, light bulbs and neon

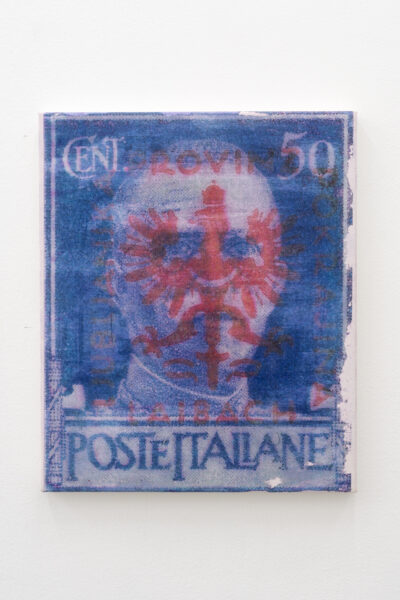

130×120×110 cm Serie Imperiale, 2023Transfer gel print on canvas

Serie Imperiale, 2023Transfer gel print on canvas

60×50 cm Blue Willow, 2023silver tray and blue porcelain

Blue Willow, 2023silver tray and blue porcelain

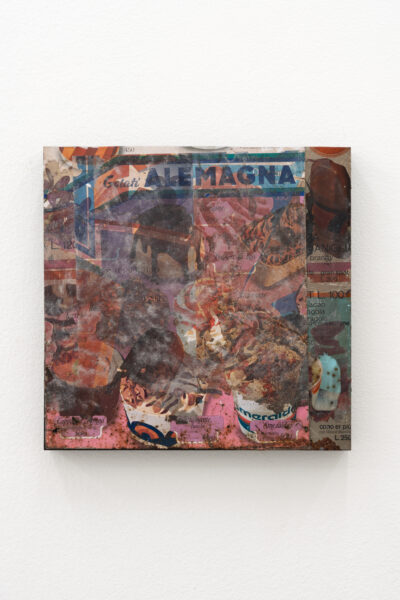

57×85 cm Diamante stampa , 2023Transfer print on tins

Diamante stampa , 2023Transfer print on tins

35×35 cm