Opening 25/09 - 25/09 - 06/11, 2019

-

Flavio Favelli

Afgacolor

Many things come together in Afgacolor, Flavio Favelli’s second show at Francesca Minini Gallery: the objects and shapes of a consolidated language – neon, assemblies and collages of mirrors, postage stamps, and Persian carpets, environments as mute encumbrances inaccessible to the viewer’s body, and painting, as copy and enlargement on plates of existing shapes and objects – all transmuted into dark color, as if all the show’s imagery emerged from sticky depths. The most remote of the artist’s forming experiences centered around the world of ancient Persia, attraction to modern Middle East, Eastern European, and Arab nations, those in which the stratification and blending of styles contrasts between new ideals and archaic customs are most evident.

Half Dinar, a 2018 solo show, featured a painting representing the colossal oil refinery depicted on a Libyan banknote in circulation during the 70s, indicator of both propaganda and fragile fantasy world and unresolved progress that ended up mingling with other images of Italy’s history and apparently unlikely contrasts not really so dissimilar in substance.

At the center of Afgacolor instead, seemingly picking up where that show left off, stands Afghanistan, somewhere the artist has never been, and in the imagination of the West, one of the most sinister and devastated places on the planet.

Never before as in this show has Favelli directed his gaze as far from the landscape in which we’ve grown accustomed to seeing him: family scenes, old houses, vacation houses, articles of outdated bourgeoisie taste, places and symbols that announce the arrival of affluence, Italian history of not-so- long-ago, the 70s and 80s that colored the artist’s childhood and early youth.

Yet even when the object is defined so sharply and seems to assume the outline of some obscure magma alien to the artist’s biography as in Agfacolor, Favelli’s works always seem to give the impression of obsessions that seem to arise from within, old family furniture, stories to be pieced together from old passports and airline tickets fished out of old drawers, images rolling past on the evening news as disturbance, infractions of the stodgy flow of everyday bourgeoisie life.

The most political (or considered as such) works Favelli has done so far – never overly elaborate or analytical but enlivened instead by fragments, contraction, and twists of meaning – derive from the same autobiographical substance. Hence, although never entirely political, they pinpoint moments of inevitable contrast between personal obsession and community life.

Although I cannot be sure these things may be seen as a key to access this new project of Favelli’s, they certainly provide an indication, but no antidote to the sense of alienation one inevitably experiences at a show like this.

The question is what Favelli sees in Afghanistan: a nation in the perpetual torment of Russian, Taliban, American war and invasion? A hideout for Al Qaeda and Isis members? Favelli’s Afghanistan is a mysterious, unattainable object, a wellspring of shapes that emerge from obscurity and darkness, from the impenetrability of a landscape never visited in person.

Afghanistan is also a frame on which fragmentary images that have sedimented in memory can be stitched together: the assassination of a president, Mohammad Najibullah, “the Ox of Kabul”, whose tortured corpse body was hung from a concrete pillar by the Talibans; an official, completely black flag adopted until the end of the 1800s; the marches of haggard militias through the desert with abandoned villages, ancient ruins, smoldering metal carcasses, and smoke columns rising in the background; the traces of the Russian imaginary world, so different and intriguing for Islamic culture.

Lastly, Afghanistan offers the occasion for an encounter – out of the corner of the eye – with the approach taken by the concept artist Boetti: assemblies of carpets based on the geometric repetition of floral patterns and vibrant contrasts of black and red become tapestries to be hung on the wall, and always with the same slant, the entirely modern and Western 20th century tradition that tends towards aniconic art and painting’s “degree zero”.

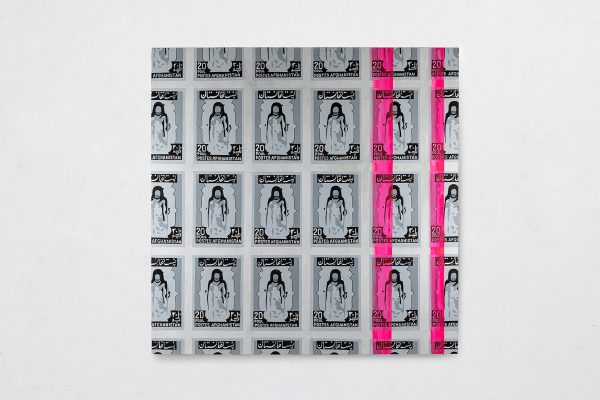

Because Afghanistan is portrayed in this show in one color: black – an elegant, deep black – or more precisely, a pervasive desire for monochrome (an aspect often evident in Favelli’s work with the appearance of a background that conceals, coats, erases), the works display the same tendency to monochrome (black and gray) the collage of postage stamps; (to silver) his new series of assemblies of mirrors; (to gold, by means of a veil of uniform paint that covers/blocks the entire structure) the parallelepiped, a minimal form, an impenetrable encumbrance that nearly fills the Gallery’s small room, an example of beauty as an end in itself that inevitably recalls the Ka’aba, albeit a ka’aba in smaller, domestic scale.

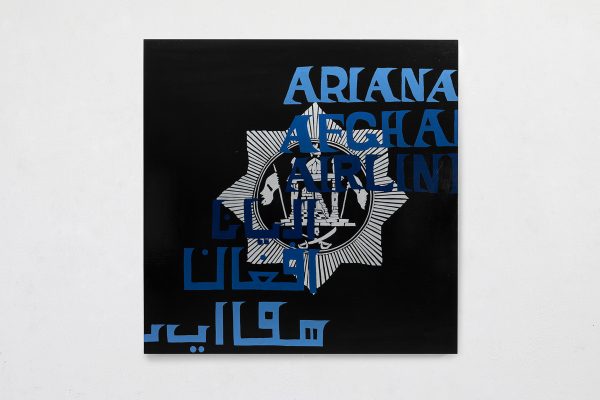

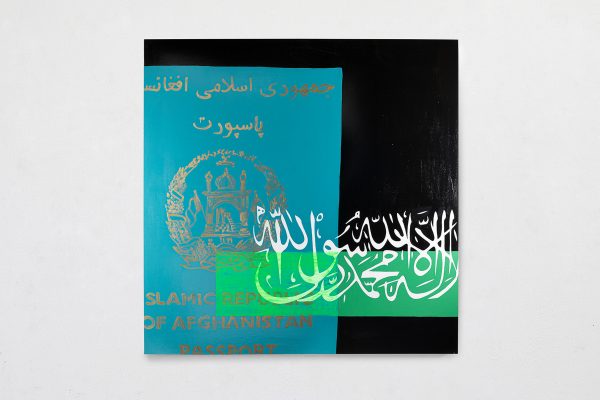

The forms in the paintings on display also stand out against black: the logo of the nation’s Ariana Airlines, (here complemented by another in close tangency with the work that addresses the Ustica tragedy in which the logo of Itavia air company provide the project with punctuation); the copy of an Afghan passport – (showing me which, Flavio informed me that recent statistics rank the conditions of the Afghan citizen – subject to the most drastic of restrictions – as the most unfortunate on earth); the logo of Kabul’s Hotel Intercontinental, the accommodation the city provides to its wealthiest foreign visitors, overwritten as in the other paintings with the Shahada creed and other writings in Arab that appear as threatening, warlike, floral outgrowths.

The neon Afgacolor work, obtained through a simple metathesis or rearrangement inside the old name/logo of the popular brand of photographic film, finally pushes Afghanistan and its vivid contrasts onto familiar ground and a time known for the democratization of photography: family snapshots or photos in exotic locations or vice-versa projects Afga colors onto black Afghanistan.

Davide Ferri

Many things come together in Afgacolor, Flavio Favelli’s second show at Francesca Minini Gallery: the objects and shapes of a consolidated language – neon, assemblies and collages of mirrors, postage stamps, and Persian carpets, environments as mute encumbrances inaccessible to the viewer’s body, and painting, as copy and enlargement on plates of existing shapes and objects – all transmuted into dark color, as if all the show’s imagery emerged from sticky depths. The most remote of the artist’s forming experiences centered around the world of ancient Persia, attraction to modern Middle East, Eastern European, and Arab nations, those in which the stratification and blending of styles contrasts between new ideals and archaic customs are most evident.

Half Dinar, a 2018 solo show, featured a painting representing the colossal oil refinery depicted on a Libyan banknote in circulation during the 70s, indicator of both propaganda and fragile fantasy world and unresolved progress that ended up mingling with other images of Italy’s history and apparently unlikely contrasts not really so dissimilar in substance.

At the center of Afgacolor instead, seemingly picking up where that show left off, stands Afghanistan, somewhere the artist has never been, and in the imagination of the West, one of the most sinister and devastated places on the planet.

Never before as in this show has Favelli directed his gaze as far from the landscape in which we’ve grown accustomed to seeing him: family scenes, old houses, vacation houses, articles of outdated bourgeoisie taste, places and symbols that announce the arrival of affluence, Italian history of not-so- long-ago, the 70s and 80s that colored the artist’s childhood and early youth.

Yet even when the object is defined so sharply and seems to assume the outline of some obscure magma alien to the artist’s biography as in Agfacolor, Favelli’s works always seem to give the impression of obsessions that seem to arise from within, old family furniture, stories to be pieced together from old passports and airline tickets fished out of old drawers, images rolling past on the evening news as disturbance, infractions of the stodgy flow of everyday bourgeoisie life.

The most political (or considered as such) works Favelli has done so far – never overly elaborate or analytical but enlivened instead by fragments, contraction, and twists of meaning – derive from the same autobiographical substance. Hence, although never entirely political, they pinpoint moments of inevitable contrast between personal obsession and community life.

Although I cannot be sure these things may be seen as a key to access this new project of Favelli’s, they certainly provide an indication, but no antidote to the sense of alienation one inevitably experiences at a show like this.

The question is what Favelli sees in Afghanistan: a nation in the perpetual torment of Russian, Taliban, American war and invasion? A hideout for Al Qaeda and Isis members? Favelli’s Afghanistan is a mysterious, unattainable object, a wellspring of shapes that emerge from obscurity and darkness, from the impenetrability of a landscape never visited in person.

Afghanistan is also a frame on which fragmentary images that have sedimented in memory can be stitched together: the assassination of a president, Mohammad Najibullah, “the Ox of Kabul”, whose tortured corpse body was hung from a concrete pillar by the Talibans; an official, completely black flag adopted until the end of the 1800s; the marches of haggard militias through the desert with abandoned villages, ancient ruins, smoldering metal carcasses, and smoke columns rising in the background; the traces of the Russian imaginary world, so different and intriguing for Islamic culture.

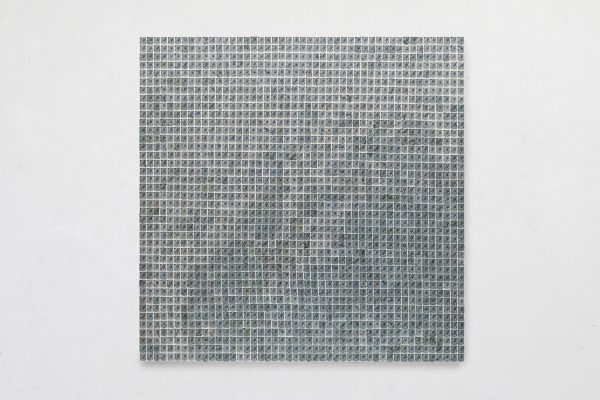

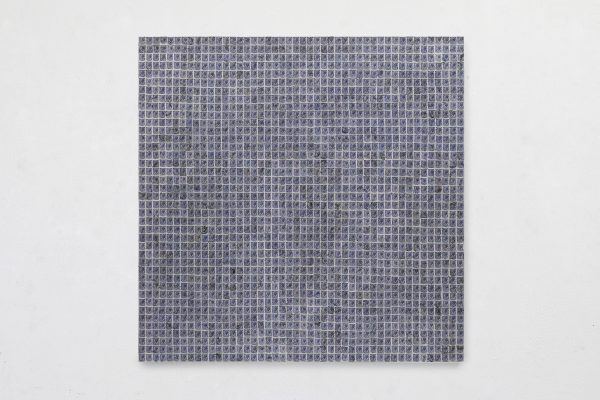

Lastly, Afghanistan offers the occasion for an encounter – out of the corner of the eye – with the approach taken by the concept artist Boetti: assemblies of carpets based on the geometric repetition of floral patterns and vibrant contrasts of black and red become tapestries to be hung on the wall, and always with the same slant, the entirely modern and Western 20th century tradition that tends towards aniconic art and painting’s “degree zero”.

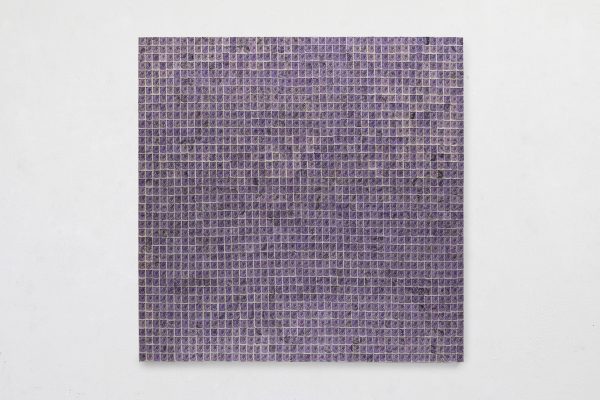

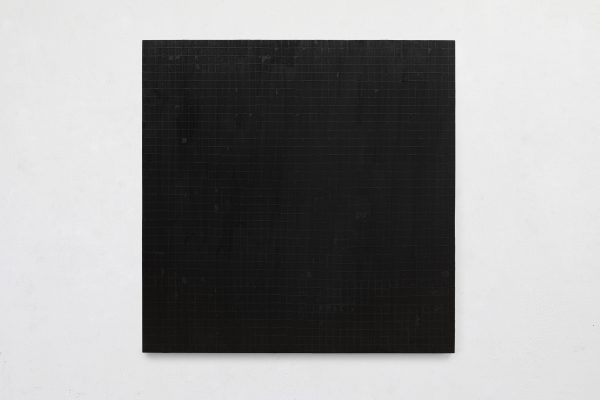

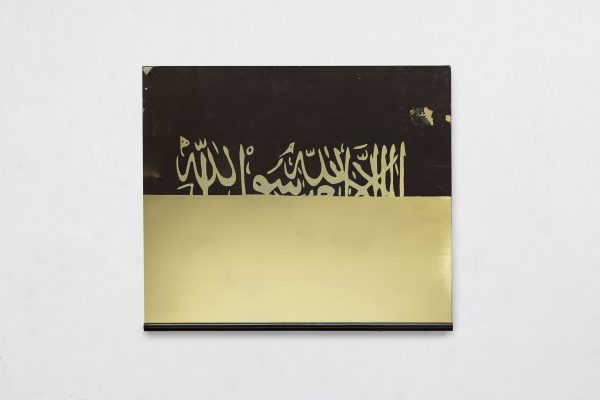

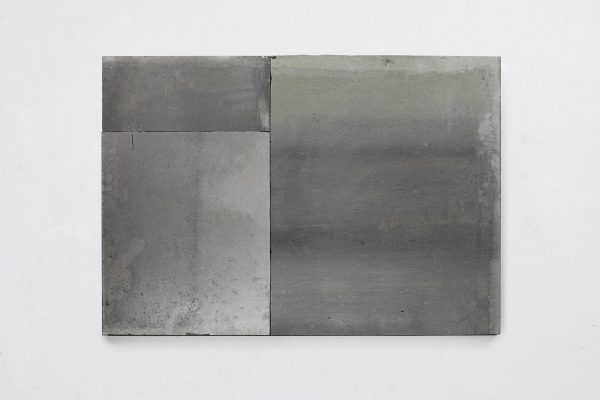

Because Afghanistan is portrayed in this show in one color: black – an elegant, deep black – or more precisely, a pervasive desire for monochrome (an aspect often evident in Favelli’s work with the appearance of a background that conceals, coats, erases), the works display the same tendency to monochrome (black and gray) the collage of postage stamps; (to silver) his new series of assemblies of mirrors; (to gold, by means of a veil of uniform paint that covers/blocks the entire structure) the parallelepiped, a minimal form, an impenetrable encumbrance that nearly fills the Gallery’s small room, an example of beauty as an end in itself that inevitably recalls the Ka’aba, albeit a ka’aba in smaller, domestic scale.

The forms in the paintings on display also stand out against black: the logo of the nation’s Ariana Airlines, (here complemented by another in close tangency with the work that addresses the Ustica tragedy in which the logo of Itavia air company provide the project with punctuation); the copy of an Afghan passport – (showing me which, Flavio informed me that recent statistics rank the conditions of the Afghan citizen – subject to the most drastic of restrictions – as the most unfortunate on earth); the logo of Kabul’s Hotel Intercontinental, the accommodation the city provides to its wealthiest foreign visitors, overwritten as in the other paintings with the Shahada creed and other writings in Arab that appear as threatening, warlike, floral outgrowths.

The neon Afgacolor work, obtained through a simple metathesis or rearrangement inside the old name/logo of the popular brand of photographic film, finally pushes Afghanistan and its vivid contrasts onto familiar ground and a time known for the democratization of photography: family snapshots or photos in exotic locations or vice-versa projects Afga colors onto black Afghanistan.

Davide Ferri

Afgacolor, 2019assemblage of signs

Afgacolor, 2019assemblage of signs

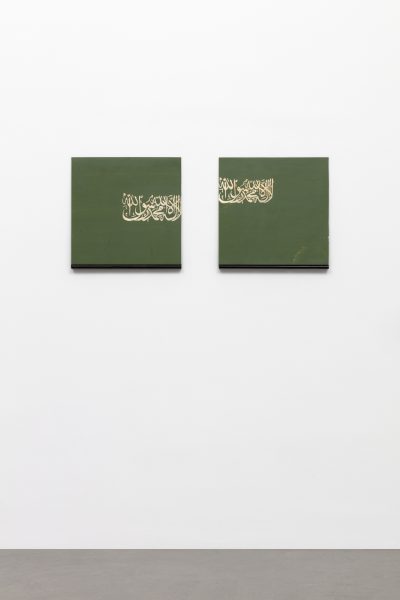

55×165×10 cm Verde Shahada, 2019scratched mirror on board

Verde Shahada, 2019scratched mirror on board

43×43 cm each Hotel Kabul, 2019enamel on board

Hotel Kabul, 2019enamel on board

150×150 cm Ariana Afghan Air, 2019enamel on board

Ariana Afghan Air, 2019enamel on board

150×150 cm Islamic Republic, 2019enamel on board

Islamic Republic, 2019enamel on board

150×150 cm Buddha, 2019enamel on board

Buddha, 2019enamel on board

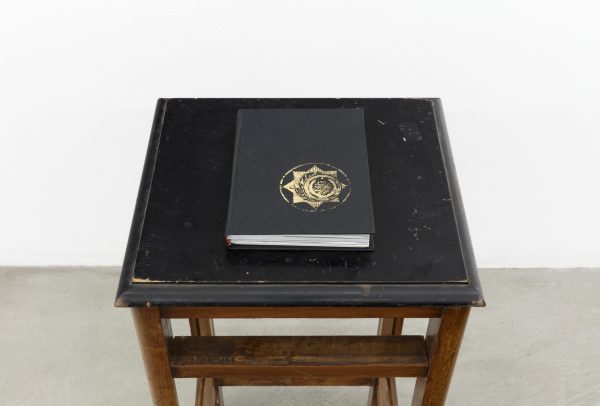

150×150 cm Libro 1, 2019ink on catalog pages

Libro 1, 2019ink on catalog pages

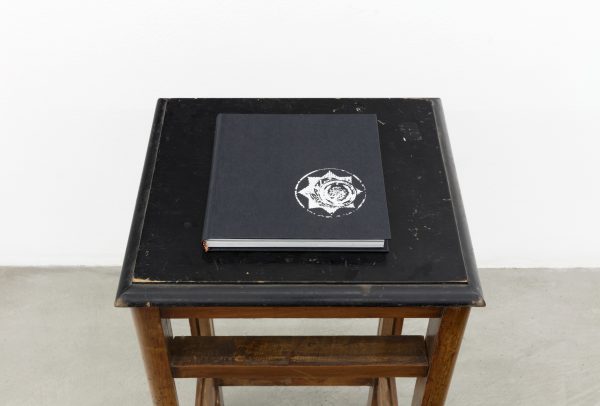

21,4×16,8×2,7 cm Libro 2, 2019ink on catalog pages

Libro 2, 2019ink on catalog pages

21,4×20,5×1,9 cm Fiori Afghan K1, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

Fiori Afghan K1, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

160×160 cm Fiori Afghan K2, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

Fiori Afghan K2, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

160×160 cm Fiori Afghan K3, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

Fiori Afghan K3, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

160×160 cm Fiori Afghan K4, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

Fiori Afghan K4, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

160×160 cm Fiori Afghan K5, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

Fiori Afghan K5, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

160×160 cm Fiori Afghan K6, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

Fiori Afghan K6, 2019assemblage of afghan carpets

160×160 cm Silver Khan, 2019enamel on board

Silver Khan, 2019enamel on board

49×49 cm Fluo Shahada, 2019enamel on board

Fluo Shahada, 2019enamel on board

65×65 cm Stendardo Grigio Verde, 2019stamps on board

Stendardo Grigio Verde, 2019stamps on board

90×90 cm Stendardo Piombo, 2019stamps on board

Stendardo Piombo, 2019stamps on board

90×90 cm Stendardo Malva, 2019stamps on board

Stendardo Malva, 2019stamps on board

90×90 cm Stendardo Nero, 2019stamps on board

Stendardo Nero, 2019stamps on board

90×90 cm Gold Shahada, 2019scratched mirror on board

Gold Shahada, 2019scratched mirror on board

53×64 cm Moro Shahada, 2019scratched mirror on board

Moro Shahada, 2019scratched mirror on board

59×59 cm Kabul Cielo, 2019assemblage of mercury mirrors

Kabul Cielo, 2019assemblage of mercury mirrors

70×100 cm Kabul Cielo, 2019assemblage of mercury mirrors

Kabul Cielo, 2019assemblage of mercury mirrors

50×70 cm