11/05 - 30/07, 2016

-

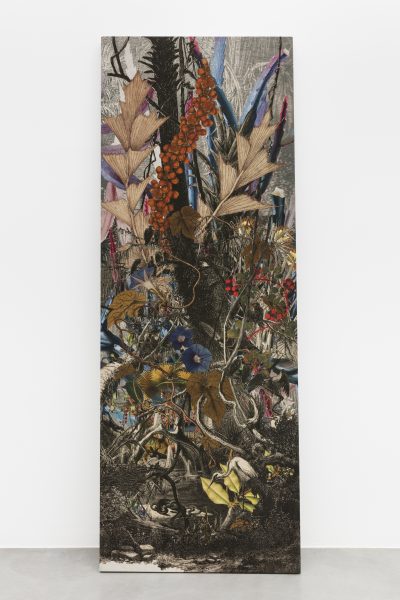

Francesco Simeti

Armed, Barbed and Halberd-Shaped

Curated by Nicola Ricciardi

Mugwort, thornapple, goldenrod and poppy. Arise, children of the weedland, proletariat of the plant kingdom, and topple the thrones of the nobler horticultural flora, chop off their hypercivilized, hybridized heads. Gird yourselves and gallop out to overthrow the rose, queen of the garden. The Romantics and poets, Emerson and Thoreau, are with you. Gerard Manley Hopkins is singing, “Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet”! But then the gardener’s hand swoops down—as maker, warden and judge of artificial landscapes—and the revolt is already quelled. A hoe to the roots and the weeds have been extirpated. Every garden tended by man is a failed coup-d’état, a foundered revolution.

Not this time, not in this show. The garden designed by Francesco Simeti has no room for roses: the victors on this battlefield are amaranth and nettle, burdock and nightshade. Worlds away from the West’s coveted utopia of tamed green spaces eternally in flower, where the bugs never bite and the leaves never sting. The landscape dreamed up by Simeti does not echo the reassuring repetitiveness of flowerbeds, the hierarchical order of botanical gardens, the geometric precision of tilled fields: it is not inspired by Monet’s flowery idylls, but rather by Charles Burchfield’s swamplands, unplowed meadows and abandoned lots.

Simeti’s plants grow on plinths, cut through concrete like knife blades, climb over the masonry to cover entire walls. Their vitality, vehemence and sovereignty is celebrated, yet at the same time, seems negated: the materials they are made of are inorganic; their forms sculpted by the very hands they tend to fear, those of man. In this marsh-garden, where even the mist is manmade, photosynthesis has given way to lost-wax casting, to the kiln. The boundary between nature and culture dissipates like fog, everything is wild and everything is crafted.

Hence the first flash of insight: these bronze flowers, clay leaves and cloth shrubs proclaim the impossibility of imagining wild nature without human nature; from the loss of biodiversity to climate change, the ecosystem is itself an anthropic artifact. Some form of gardening is now considered inevitable even in oasis, sanctuaries and reserves—in the places we would preserve as monuments to our own absence. Simeti does not merely point out this paradox, but by sculpting his weeds like halberds, helmets, and shields, presents us with one more truth:

however certain we may be that nature’s survival depends only on us, nature has proven capable of defending itself on its own. With every push or pull man has given to the biosphere, plants have always responded by sharpening their weapons, honing their agility, gearing up to survive our impact. What are weeds but an empirical demonstration of nature’s capability to withstand us? On the other hand, whether humans can adapt to the changes brought about by their own actions has yet to be seen. So who is more vulnerable and unarmed—Simeti seems to ask—who really needs to be defended: us or them?

Mugwort, thornapple, goldenrod and poppy. Arise, children of the weedland, proletariat of the plant kingdom, and topple the thrones of the nobler horticultural flora, chop off their hypercivilized, hybridized heads. Gird yourselves and gallop out to overthrow the rose, queen of the garden. The Romantics and poets, Emerson and Thoreau, are with you. Gerard Manley Hopkins is singing, “Long live the weeds and the wilderness yet”! But then the gardener’s hand swoops down—as maker, warden and judge of artificial landscapes—and the revolt is already quelled. A hoe to the roots and the weeds have been extirpated. Every garden tended by man is a failed coup-d’état, a foundered revolution.

Not this time, not in this show. The garden designed by Francesco Simeti has no room for roses: the victors on this battlefield are amaranth and nettle, burdock and nightshade. Worlds away from the West’s coveted utopia of tamed green spaces eternally in flower, where the bugs never bite and the leaves never sting. The landscape dreamed up by Simeti does not echo the reassuring repetitiveness of flowerbeds, the hierarchical order of botanical gardens, the geometric precision of tilled fields: it is not inspired by Monet’s flowery idylls, but rather by Charles Burchfield’s swamplands, unplowed meadows and abandoned lots.

Simeti’s plants grow on plinths, cut through concrete like knife blades, climb over the masonry to cover entire walls. Their vitality, vehemence and sovereignty is celebrated, yet at the same time, seems negated: the materials they are made of are inorganic; their forms sculpted by the very hands they tend to fear, those of man. In this marsh-garden, where even the mist is manmade, photosynthesis has given way to lost-wax casting, to the kiln. The boundary between nature and culture dissipates like fog, everything is wild and everything is crafted.

Hence the first flash of insight: these bronze flowers, clay leaves and cloth shrubs proclaim the impossibility of imagining wild nature without human nature; from the loss of biodiversity to climate change, the ecosystem is itself an anthropic artifact. Some form of gardening is now considered inevitable even in oasis, sanctuaries and reserves—in the places we would preserve as monuments to our own absence. Simeti does not merely point out this paradox, but by sculpting his weeds like halberds, helmets, and shields, presents us with one more truth:

however certain we may be that nature’s survival depends only on us, nature has proven capable of defending itself on its own. With every push or pull man has given to the biosphere, plants have always responded by sharpening their weapons, honing their agility, gearing up to survive our impact. What are weeds but an empirical demonstration of nature’s capability to withstand us? On the other hand, whether humans can adapt to the changes brought about by their own actions has yet to be seen. So who is more vulnerable and unarmed—Simeti seems to ask—who really needs to be defended: us or them?

The wilds V, 2015Sodafire and glaze ceramic

The wilds V, 2015Sodafire and glaze ceramic

38×20×21 cm The wilds VI, 2015Sodafire and glaze ceramic

The wilds VI, 2015Sodafire and glaze ceramic

41×30×30 cm The wilds XIV, 2015Sodafire and glaze ceramic

The wilds XIV, 2015Sodafire and glaze ceramic

67×25×25 cm Two-ranked, 2016bronze

Two-ranked, 2016bronze

245×36×5 cm Axillary, 2016

Axillary, 2016

bronze

245×25×14 cm Helicoid, 2016bronze

Helicoid, 2016bronze

245×23×21 cm Runcinate, 2016bronze

Runcinate, 2016bronze

245×31×14 cm Spadix, 2016bronze

Spadix, 2016bronze

245×17×14 cm Virgate, 2016

Virgate, 2016

bronze

245×33×17 cm Spathe bearing, 2016bronze

Spathe bearing, 2016bronze

245×42×18 cm Black reef I, 2016

Black reef I, 2016

ceramic

56×23×13 cm Indian Head, 2016

Indian Head, 2016

print on linen

230×85 cm

Cypress swamp, 2016print on linen

Cypress swamp, 2016print on linen

226×85 cm Centaurea, 2016ceramic

Centaurea, 2016ceramic

18×30×40 cm Awl-shaped, 2016ceramic

Awl-shaped, 2016ceramic

52×14×10 cm Billows III, 2015ceramic

Billows III, 2015ceramic

dimensions variable The wilds, 2015Ceramic

The wilds, 2015Ceramic

26×16×18 cm

24 x 15 x 18 cm Distichous, Corniculate, Runcinate, 2016watercolour on paper

Distichous, Corniculate, Runcinate, 2016watercolour on paper

45,5×30 cm each