Opening 17/09 - 18/09 - 30/11, 2024

-

Jacopo Benassi

Sàlvati Salvàti

flashes of an exploding stage

With an expanded practice encompassing installation, painting, performance and sculpture, Jacopo Benassi is recognized for his unique take on photography. Since the 1980s he has documented agents and communities belonging to what is broadly understood as the underground, often affiliated with the music scene. While portraying social environments regularly excluded from mainstream visibility, his images are both a powerful statement against one-dimensional conceptions of society, as well as, and more importantly, testaments of the vital energy emerging from its margins. In this sense, Benassi’s work lubricates stale notions of self and other, inserting divergence into homogeneity and liberation into repression, promoting other ways of conceiving and being in the world.

The employment of flash is arguably one of the most defining features of the artist’s practice and a sharp lens through which to engage with his body of work. Emerging out of photography’s developments and, in particular, Robert Bunsen and Henry Roscoe’s experiments with magnesium in the mid-1800s, flash refers both to the burst of light as well as the light producing unit. The term is also used to describe fleeting apparitions or explosion-like phenomena, the latter echoing its original use as an ignition based pyrotechnic lighting process. Benassi’s work spills out of his biography. Realising homosexual attraction was considered a socially deviant emotion was an early moment of spark in his life and was followed by his coming out, which coincided with the embrace of photography. In Benassi’s life, two intersecting flash-like explosions came together to propel the big bang of his practice.

Whereas flash’s normative function is to illuminate what the camera might not be able to capture due to poor light conditions, in reality, flash conceals as much as it reveals: its brief and intense illumination might produce contrasting highly lit sections alongside darkened areas on the edges of an image. As it follows, Benassi’s recurrent employment of flash is densely resonant: on the one side inverting stable social dynamics of visibility and power, on the other, bringing to light flash’s paradoxical silencing capabilities. By lending bursts of light to silenced figures and situations, his images function both as defiant gestures and self- reflexive critical reflections.

In Sàlvati Salvàti, loosely translated as Save Yourself Saved, Benassi reframes the exhibition as an apparatus to question its visitors, preventing a detached stance. Choreographed by a chaotic barricade, the gallery space embodies the conflicted period we are inhabiting and underlines the impossibility of an outside. In Europe and among other examples, barricades propose echoes of the May 68 and the French Revolution, pivotal references to political imaginaries underpinning current social configurations. At the same time, its belligerent quality might also be understood as direct reference to ongoing conflicts in places such as Ukraine, Palestine or Sudan. Via its intrinsic configuration, the barricade also manifests as a marker of our contested societies, progressively defined by processes of fragmentation and polarization. While combining these readings, because of its gallery setting the barricade also voices questions related to the agency of art.

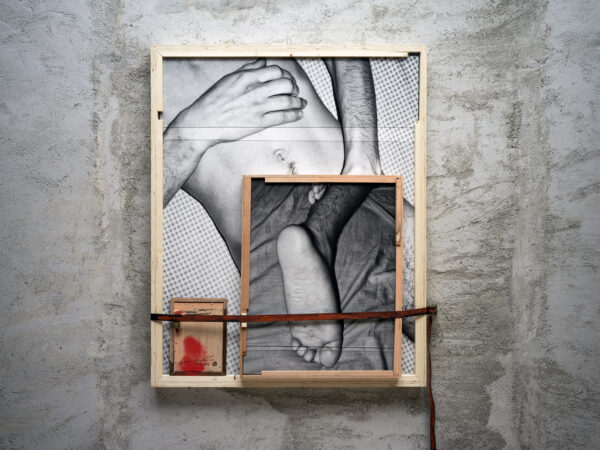

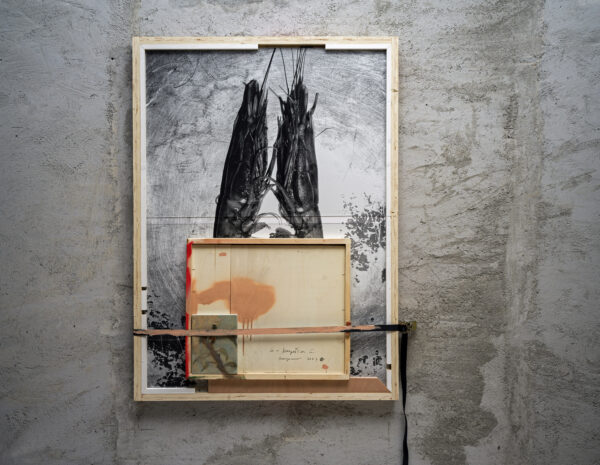

Whereas Benassi might speak from a subjective point of view, his work engages with wide social issues, and, here in particular, connects with the generalised anger-driven, confused mindset of our present times. Josh Cohen, psychoanalyst and emeritus professor of English at Goldsmiths, University of London, argues that feelings of anger are a “defining emotional texture of our daily social and political lives, giving rise to a pervasive atmosphere of mutual fear, suspicion and accusation, in which any perception of difference – cultural, ideological, racial, sexual, class – shades quickly into the assumption of enmity.” Benassi’s barricade seems to embody Cohen’s assumptions and reframes the gallery space as a public forum. The central installation is accompanied by sculptural assemblages of photographs, where images cover other images in sets bounded by tense straps.

These works enhance the exhibition’s reverberations of our critical context: the hidden images manifesting simultaneously as lighthouses and hideouts of silenced, repressed forces, blocking the represented scenes to stimulate an imaginative interaction. Likewise, understood as tense near-to-collapse instances of inclusion and exclusion, the strained strapped sets project menacing possibilities of social explosions, actualizing a liminal position: preceding bursts of energy as well as illustrating their aftermath. The four performances presented during the exhibition period intensify these tensions, creating ephemeral live communities of strangers by placing audience members in the same place at the same time, a contrast with the diffused pace of a common gallery visit. The proposed detonation of dominant narratives is notably manifested by Brutal Casual, where photographic authorship is given to the public. In Sàlvati Salvàti the unknown materialises as a porous form open to multiple possibilities.

Numerous signs alert to the dangers of a reiteration of the 1930s, a period similar to what Gramsci defined as a decaying period, where the new world struggles to be born and monsters emerge. Addressing the current post-Brexit climate and attempting to offer a way forward, Josh Cohen argues that in order to resist far-right populism “it is not so much the rational appeal to facts we need to be making so much as contact with the depth and complexity of our feelings.” For the psychoanalyst “lurking under (…) coiled anger is a rich and complex seam of emotional experience we should be listening to (…), instead of to the noisy slogans drowning it out.” In Sàlvati Salvàti Benassi offers both an bewildered flashing warning and a stage where anger and confusion can be experienced and expressed collectively. Instead of a death-drive deepening dispute, we find a space to uncover possibilities and bypass excluding boundaries, categories and understandings. We are invited to a space of conflict where we can enact and reflect our feelings, overcoming the fear which eats the soul.

João Laia

PERFORMANCES PROGRAM:

17 September 2024

Yes not war

with Khan of Finland

3 October 2024

Brutal Casual

with Lady Maru

23 October 2024

Sassi

with Luciano Chessa and Marco Mazzoni

6 November 2024

INNO

with Lamante and Michele Lombardelli

flashes of an exploding stage

With an expanded practice encompassing installation, painting, performance and sculpture, Jacopo Benassi is recognized for his unique take on photography. Since the 1980s he has documented agents and communities belonging to what is broadly understood as the underground, often affiliated with the music scene. While portraying social environments regularly excluded from mainstream visibility, his images are both a powerful statement against one-dimensional conceptions of society, as well as, and more importantly, testaments of the vital energy emerging from its margins. In this sense, Benassi’s work lubricates stale notions of self and other, inserting divergence into homogeneity and liberation into repression, promoting other ways of conceiving and being in the world.

The employment of flash is arguably one of the most defining features of the artist’s practice and a sharp lens through which to engage with his body of work. Emerging out of photography’s developments and, in particular, Robert Bunsen and Henry Roscoe’s experiments with magnesium in the mid-1800s, flash refers both to the burst of light as well as the light producing unit. The term is also used to describe fleeting apparitions or explosion-like phenomena, the latter echoing its original use as an ignition based pyrotechnic lighting process. Benassi’s work spills out of his biography. Realising homosexual attraction was considered a socially deviant emotion was an early moment of spark in his life and was followed by his coming out, which coincided with the embrace of photography. In Benassi’s life, two intersecting flash-like explosions came together to propel the big bang of his practice.

Whereas flash’s normative function is to illuminate what the camera might not be able to capture due to poor light conditions, in reality, flash conceals as much as it reveals: its brief and intense illumination might produce contrasting highly lit sections alongside darkened areas on the edges of an image. As it follows, Benassi’s recurrent employment of flash is densely resonant: on the one side inverting stable social dynamics of visibility and power, on the other, bringing to light flash’s paradoxical silencing capabilities. By lending bursts of light to silenced figures and situations, his images function both as defiant gestures and self- reflexive critical reflections.

In Sàlvati Salvàti, loosely translated as Save Yourself Saved, Benassi reframes the exhibition as an apparatus to question its visitors, preventing a detached stance. Choreographed by a chaotic barricade, the gallery space embodies the conflicted period we are inhabiting and underlines the impossibility of an outside. In Europe and among other examples, barricades propose echoes of the May 68 and the French Revolution, pivotal references to political imaginaries underpinning current social configurations. At the same time, its belligerent quality might also be understood as direct reference to ongoing conflicts in places such as Ukraine, Palestine or Sudan. Via its intrinsic configuration, the barricade also manifests as a marker of our contested societies, progressively defined by processes of fragmentation and polarization. While combining these readings, because of its gallery setting the barricade also voices questions related to the agency of art.

Whereas Benassi might speak from a subjective point of view, his work engages with wide social issues, and, here in particular, connects with the generalised anger-driven, confused mindset of our present times. Josh Cohen, psychoanalyst and emeritus professor of English at Goldsmiths, University of London, argues that feelings of anger are a “defining emotional texture of our daily social and political lives, giving rise to a pervasive atmosphere of mutual fear, suspicion and accusation, in which any perception of difference – cultural, ideological, racial, sexual, class – shades quickly into the assumption of enmity.” Benassi’s barricade seems to embody Cohen’s assumptions and reframes the gallery space as a public forum. The central installation is accompanied by sculptural assemblages of photographs, where images cover other images in sets bounded by tense straps.

These works enhance the exhibition’s reverberations of our critical context: the hidden images manifesting simultaneously as lighthouses and hideouts of silenced, repressed forces, blocking the represented scenes to stimulate an imaginative interaction. Likewise, understood as tense near-to-collapse instances of inclusion and exclusion, the strained strapped sets project menacing possibilities of social explosions, actualizing a liminal position: preceding bursts of energy as well as illustrating their aftermath. The four performances presented during the exhibition period intensify these tensions, creating ephemeral live communities of strangers by placing audience members in the same place at the same time, a contrast with the diffused pace of a common gallery visit. The proposed detonation of dominant narratives is notably manifested by Brutal Casual, where photographic authorship is given to the public. In Sàlvati Salvàti the unknown materialises as a porous form open to multiple possibilities.

Numerous signs alert to the dangers of a reiteration of the 1930s, a period similar to what Gramsci defined as a decaying period, where the new world struggles to be born and monsters emerge. Addressing the current post-Brexit climate and attempting to offer a way forward, Josh Cohen argues that in order to resist far-right populism “it is not so much the rational appeal to facts we need to be making so much as contact with the depth and complexity of our feelings.” For the psychoanalyst “lurking under (…) coiled anger is a rich and complex seam of emotional experience we should be listening to (…), instead of to the noisy slogans drowning it out.” In Sàlvati Salvàti Benassi offers both an bewildered flashing warning and a stage where anger and confusion can be experienced and expressed collectively. Instead of a death-drive deepening dispute, we find a space to uncover possibilities and bypass excluding boundaries, categories and understandings. We are invited to a space of conflict where we can enact and reflect our feelings, overcoming the fear which eats the soul.

João Laia

PERFORMANCES PROGRAM:

17 September 2024

Yes not war

with Khan of Finland

3 October 2024

Brutal Casual

with Lady Maru

23 October 2024

Sassi

with Luciano Chessa and Marco Mazzoni

6 November 2024

INNO

with Lamante and Michele Lombardelli

Panorama della spiaggia di Pachino (Sicilia), 2024Panorama della spiaggia di Pachino (Sicilia), 2024

Panorama della spiaggia di Pachino (Sicilia), 2024Panorama della spiaggia di Pachino (Sicilia), 2024 La fine del mondo?, 2024Acrylic on canvas, fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

La fine del mondo?, 2024Acrylic on canvas, fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

152×127,5×14 cm La fine del mondo?, 2024Acrylic on canvas, fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

La fine del mondo?, 2024Acrylic on canvas, fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

147×115×14 cm Turner is not dead!, 2024Acrylic on canvas, fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

Turner is not dead!, 2024Acrylic on canvas, fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

84,5×124,5×11,5 cm Autoritratto nudo a Pachino (Sicilia), 2024Fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

Autoritratto nudo a Pachino (Sicilia), 2024Fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

131×110×14 cm Frocio (archivio), 2024Fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

Frocio (archivio), 2024Fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

131×112×14,5 cm Autoritratto in Pantofole, 2024Acrylic on canvas, fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

Autoritratto in Pantofole, 2024Acrylic on canvas, fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

114,5×149×11 cm Duello con il sole, 2024Fine art photo print, artist frame

Duello con il sole, 2024Fine art photo print, artist frame

130×104,5×9,5 cm

Edition of 3 Io e Augustin in spiaggia a Pachino (Sicilia), 2024Acrylic on canvas, fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

Io e Augustin in spiaggia a Pachino (Sicilia), 2024Acrylic on canvas, fine art photo prints, artist frames, wooden clips, strap

147×112×11 cm Duello con il sole, 2024Fine art photo print, artist frame

Duello con il sole, 2024Fine art photo print, artist frame

130×104,5×9,5 cm

Edition of 3 Estate 2024, 2024Concrete, rubber

Estate 2024, 2024Concrete, rubber

20×30×35 cm Barricata, 2024Concrete, tubular scaffolds, multidirectional clamps, leather

Barricata, 2024Concrete, tubular scaffolds, multidirectional clamps, leather

85×12×35 cm Barricata, 2024Concrete, tubular scaffolds, multidirectional clamps, plaster

Barricata, 2024Concrete, tubular scaffolds, multidirectional clamps, plaster

80×12×26 cm Barricata, 2024Concrete, tubular scaffolds, multidirectional clamps, plaster

Barricata, 2024Concrete, tubular scaffolds, multidirectional clamps, plaster

80×43×33 cm Sàlvati Salvàti, 2024speakers, vynil

Sàlvati Salvàti, 2024speakers, vynil

88,5×40×45 cm