Opening 19/03 - 20/03 - 10/05, 2025

REVIVAL

With works by Phoebe Collings-James, Denzil Forrester, and Kate Spencer Stewart.

Curated by Giulia Civardi.

The first in a series of exhibitions that explore intergenerational dialogues and connections between visual arts and sound. Considering the gallery as a device that shapes cultural values and market trends, as well as historical and personal narratives, Revival questions ideas of timelessness, cycles of consumption and exchange. What do these dialogues awaken, renew or invite to live again? And what do they reveal at a precise moment?

Every summer in London, my neighbours gathered around monumental sound systems, listening to dub music until late. The reverberations from the garden created a hypnotic and meditative soundscape that connected me to my desires, the space and time I inhabited. When dub first came out, people were astonished. Emerging in Jamaica in the late 1960s and arriving in cinemas and homes turned into dance halls across the UK, this way of making music was filled with echoes and repetitions. The making-process involved copying and manipulating vocal or instrumental fragments of existing sound pieces onto basslines and into new hybrid tracks. Dub influenced many subsequent music genres – from electronica to hip-hop, post-punk and ambient rock – transcending temporal and cultural boundaries. In addition to creating immersive sonic environments, this music formed a space for collective resistance, speaking of experiences where people, especially of African Caribbean descent and of mixed backgrounds, were separated from their places of origin. Even today, these sounds convey a sense of community and spiritual transformation, bringing people home. If we consider that the word ‘dub’ was used for the first time in a filmic context to merge images and voices, how could this rhythm manifest visually?

Starting from the structure of dub music, which speaks of rupture and repair, something that leaves and returns, the exhibition observes through the works on paper and paintings of Denzil Forrester and Kate Spencer Stewart and the sculptures of Phoebe Collings-James, repeated visual gestures, felt and revised under new visual forms. The artists have in common strong connections with music, not only dub, but also genres that emerged from this style. They also share a process of reinterpretation of art historical and socio-political traditions, which still shape contemporary art and help us understand our positions as subjects in continuous formation. As sociologist Stuart Hall affirms, it is by ‘detouring’ through pasts that we can produce ourselves anew as subjects. “It is therefore not a question of what our traditions make of us, so much as what we make of our traditions. […] Culture is not a matter of ontology, of being, but of becoming”.

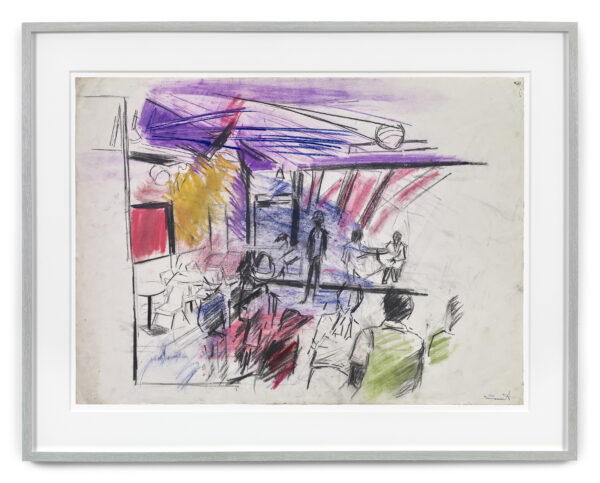

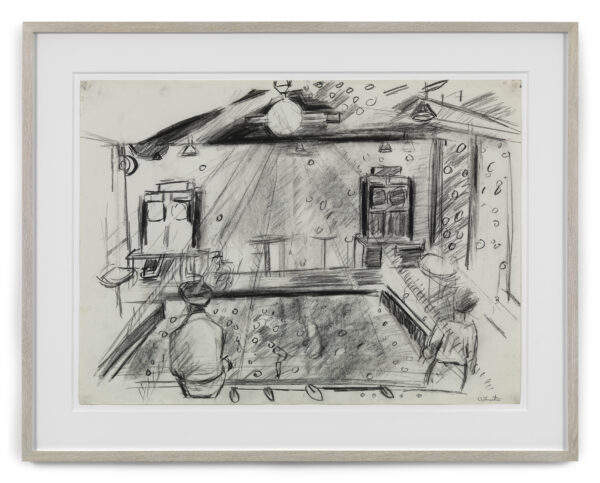

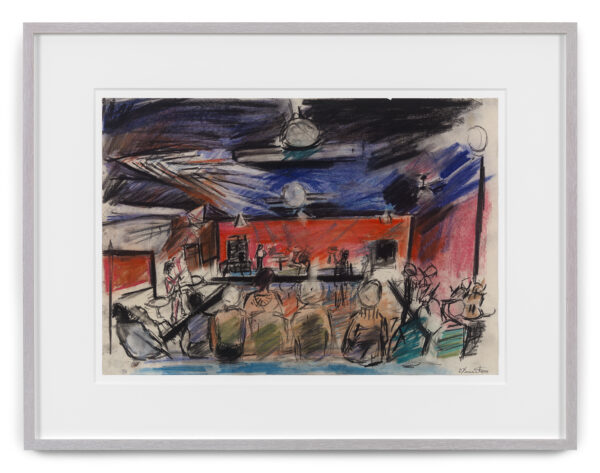

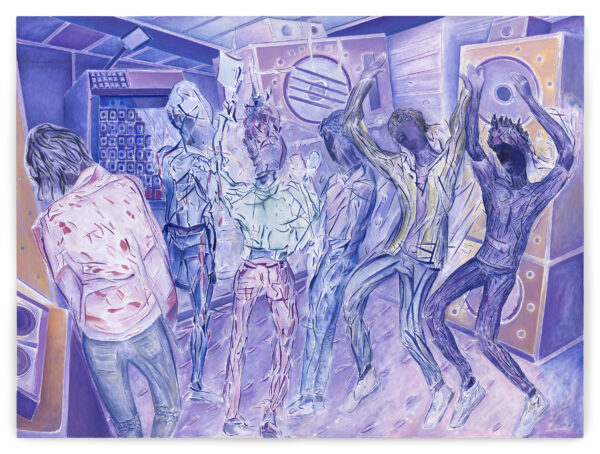

For over thirty years, Denzil Forrester (b. 1956, Grenada; lives in Cornwall, UK) has captured scenes from nightclubs and dance halls. Drawing in the dark with pastels and charcoal, without seeing clearly what he is doing, Forrester records on paper the rhythmic movements of people, sensing their joy and sadness, their vigour and desire. He then returns to the studio in the morning to continue painting. This deep, almost transcendental connection with music emerges in his practice through constant engagement with dub. As Denzil attests, ‘Dub music is like a noise that intoxicates you and gets into your system. You’re there, mesmerised, and it can take about half an hour to get used to this music. And after you get used to it, oh…’. This rhythmic experience emerges in his paintings and works on paper, both thematically and formally. As in the repetitive baselines of dub tracks, suddenly interrupted by echoing noises and booms, in the painting Dub Dance (1993), the colours move on different frequencies and gradations, following a harmony first, then becoming strong and flashing. The light is fragmented as if reflected by a disco ball, breaking bodies into distorted and enchanting shapes. The close-up, fluid figures in Boom Boom Echoes (2023) invite the viewer to be part of the scene. Although the works document a historical and cultural scenario of dance halls and music scenes from the eighties in London, these are not nostalgic representations stuck in that period. His works embody the energy of people who continue to gather, mixing stories and cultures. Forrester’s rich oeuvre, infused with sound systems, purple lights and electric bodies, becomes a visual universe carrying traces of intergenerational stories and hybrid identities echoing over time.

With an interest in non-linear narrative and symbolic language, Phoebe Collings-James (b. 1987, London, UK; lives in London, UK) incorporates sound into her sculptural practice for its spiritual and transformative power. In Joy comes with the morning [V3], 2025 – a sound installation composed of a ceramic bell as an amplifier and a water vessel – the sounds of the sea and a metropolis blend with voices reciting poetry, and noises of trumpets and drums. Some of the recordings taken from the film Our Song (Jim McKay, 2000) tell the story of young girls from Brooklyn who find a sense of belonging and expression by playing musical instruments in a community band. While the sounds of wind instruments and the sculpture of a trombone recall parts of the body related to breathing, the sonic waves mixed with those of water evoke a sense of fluidity. By reinterpreting the tradition of sound systems through clay, Collings-James creates a soundscape to feel the malleability of bodies, activating different emotional processes. Musical references infuse her sculptural practice with revolutionary potential. The artist draws inspiration from Rastafarian and Jamaican music, from artists such as Midnite and Ranking Anne and Barrington Levy, and other figures as examples of protest and resistance. A group of ceramic sculptures presents different interpretations of the infidel: an archetypal character that symbolises dissent and divergence from traditional dogmatic patterns, embracing its own sense of spirituality. The rounded shapes recall abstract bodies that escape consolidated positions while creating new characters that bear ancient signs: the inscriptions on the surface of the sculptures are realised with sgraffito – a technique used in sixteenth century Italian architecture and traditional African ceramics, as well as in Babylonian and Sumerian cuneiform clay tablets. By reviving ancient forms of communication while acknowledging Caribbean resistance through the materiality of clay, Collings-James challenges Eurocentric ways of constructing knowledge, giving form to a transcultural language, a new material memory.

Kate Spencer Stewart’s (b. 1984, Phoenix, AZ, US; lives in Los Angeles, US) minimal paintings depict everything and nothing. It is almost impossible to see them in photographs. We must walk around them, lower our eyes or move them in various ways to discover the details. The surface transforms with light and movement, creating voids, flashes, optical mixes, and moments of suspense. If observed long enough, the colours become intoxicating and hallucinatory; their shadow imprints on the retina like white noise in space, setting in motion a process of transcendence similar to that caused by ambient music and drone. Stewart grew up playing different instruments including the organ, piano, sax, accordion, and bass. Before exhibiting in galleries, her paintings were presented in music venues. Stewart’s process involves layering brush strokes and repetitive marks over underpainting, often in contrast to the final layer. The works echo the minimalist tradition of ‘color field’, particularly Ad Reinhardt’s signature black paintings, where colour became a subject in and of itself. Stewart’s paintings become visualisations rather than representations; they are not only objects to look at, but to look with. Gazing intently at the paintings may reveal a multitude of stories. Frag (2025) recalls the hedonistic influences of Fragonard’s Rococo; Troche (2025), a pictorial study of the pigment Rose Madder, derived from madder roots and highly sensitive to light, conjures Egyptian tombs, the ruins of Pompeii, and J.M.W. Turner’s eerie landscapes. Other ‘black studies’ evoke voids and theatrical backdrops. As the artist asks: ‘Why can’t we see the world as pure matter, pure form, pure gesture? […] Is it language that holds us back?’

___

Giulia Civardi is a curator and writer working both independently and, since 2020, as Curator & Collection Manager at Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation. She curated projects for institutions including Tate Modern, Rupert Centre for Art and Education, Kunstraum London and galleries including Gianni Manhattan for Curated by Vienna, Clima in Milan, Galerie In Situ in Paris, Madragoa in Lisbon. She regularly gives lectures and talks, and has guest lectured at Central Saint Martins, Goldsmiths University, Barbican Centre, Academy of Fine Arts Venice. She is an activist of AWI Art Workers Italia. Her writing on art and culture has been published, among the others, by NERO, Flash Art, CURA, this is tomorrow.

REVIVAL

With works by Phoebe Collings-James, Denzil Forrester, and Kate Spencer Stewart.

Curated by Giulia Civardi.

The first in a series of exhibitions that explore intergenerational dialogues and connections between visual arts and sound. Considering the gallery as a device that shapes cultural values and market trends, as well as historical and personal narratives, Revival questions ideas of timelessness, cycles of consumption and exchange. What do these dialogues awaken, renew or invite to live again? And what do they reveal at a precise moment?

Every summer in London, my neighbours gathered around monumental sound systems, listening to dub music until late. The reverberations from the garden created a hypnotic and meditative soundscape that connected me to my desires, the space and time I inhabited. When dub first came out, people were astonished. Emerging in Jamaica in the late 1960s and arriving in cinemas and homes turned into dance halls across the UK, this way of making music was filled with echoes and repetitions. The making-process involved copying and manipulating vocal or instrumental fragments of existing sound pieces onto basslines and into new hybrid tracks. Dub influenced many subsequent music genres – from electronica to hip-hop, post-punk and ambient rock – transcending temporal and cultural boundaries. In addition to creating immersive sonic environments, this music formed a space for collective resistance, speaking of experiences where people, especially of African Caribbean descent and of mixed backgrounds, were separated from their places of origin. Even today, these sounds convey a sense of community and spiritual transformation, bringing people home. If we consider that the word ‘dub’ was used for the first time in a filmic context to merge images and voices, how could this rhythm manifest visually?

Starting from the structure of dub music, which speaks of rupture and repair, something that leaves and returns, the exhibition observes through the works on paper and paintings of Denzil Forrester and Kate Spencer Stewart and the sculptures of Phoebe Collings-James, repeated visual gestures, felt and revised under new visual forms. The artists have in common strong connections with music, not only dub, but also genres that emerged from this style. They also share a process of reinterpretation of art historical and socio-political traditions, which still shape contemporary art and help us understand our positions as subjects in continuous formation. As sociologist Stuart Hall affirms, it is by ‘detouring’ through pasts that we can produce ourselves anew as subjects. “It is therefore not a question of what our traditions make of us, so much as what we make of our traditions. […] Culture is not a matter of ontology, of being, but of becoming”.

For over thirty years, Denzil Forrester (b. 1956, Grenada; lives in Cornwall, UK) has captured scenes from nightclubs and dance halls. Drawing in the dark with pastels and charcoal, without seeing clearly what he is doing, Forrester records on paper the rhythmic movements of people, sensing their joy and sadness, their vigour and desire. He then returns to the studio in the morning to continue painting. This deep, almost transcendental connection with music emerges in his practice through constant engagement with dub. As Denzil attests, ‘Dub music is like a noise that intoxicates you and gets into your system. You’re there, mesmerised, and it can take about half an hour to get used to this music. And after you get used to it, oh…’. This rhythmic experience emerges in his paintings and works on paper, both thematically and formally. As in the repetitive baselines of dub tracks, suddenly interrupted by echoing noises and booms, in the painting Dub Dance (1993), the colours move on different frequencies and gradations, following a harmony first, then becoming strong and flashing. The light is fragmented as if reflected by a disco ball, breaking bodies into distorted and enchanting shapes. The close-up, fluid figures in Boom Boom Echoes (2023) invite the viewer to be part of the scene. Although the works document a historical and cultural scenario of dance halls and music scenes from the eighties in London, these are not nostalgic representations stuck in that period. His works embody the energy of people who continue to gather, mixing stories and cultures. Forrester’s rich oeuvre, infused with sound systems, purple lights and electric bodies, becomes a visual universe carrying traces of intergenerational stories and hybrid identities echoing over time.

With an interest in non-linear narrative and symbolic language, Phoebe Collings-James (b. 1987, London, UK; lives in London, UK) incorporates sound into her sculptural practice for its spiritual and transformative power. In Joy comes with the morning [V3], 2025 – a sound installation composed of a ceramic bell as an amplifier and a water vessel – the sounds of the sea and a metropolis blend with voices reciting poetry, and noises of trumpets and drums. Some of the recordings taken from the film Our Song (Jim McKay, 2000) tell the story of young girls from Brooklyn who find a sense of belonging and expression by playing musical instruments in a community band. While the sounds of wind instruments and the sculpture of a trombone recall parts of the body related to breathing, the sonic waves mixed with those of water evoke a sense of fluidity. By reinterpreting the tradition of sound systems through clay, Collings-James creates a soundscape to feel the malleability of bodies, activating different emotional processes. Musical references infuse her sculptural practice with revolutionary potential. The artist draws inspiration from Rastafarian and Jamaican music, from artists such as Midnite and Ranking Anne and Barrington Levy, and other figures as examples of protest and resistance. A group of ceramic sculptures presents different interpretations of the infidel: an archetypal character that symbolises dissent and divergence from traditional dogmatic patterns, embracing its own sense of spirituality. The rounded shapes recall abstract bodies that escape consolidated positions while creating new characters that bear ancient signs: the inscriptions on the surface of the sculptures are realised with sgraffito – a technique used in sixteenth century Italian architecture and traditional African ceramics, as well as in Babylonian and Sumerian cuneiform clay tablets. By reviving ancient forms of communication while acknowledging Caribbean resistance through the materiality of clay, Collings-James challenges Eurocentric ways of constructing knowledge, giving form to a transcultural language, a new material memory.

Kate Spencer Stewart’s (b. 1984, Phoenix, AZ, US; lives in Los Angeles, US) minimal paintings depict everything and nothing. It is almost impossible to see them in photographs. We must walk around them, lower our eyes or move them in various ways to discover the details. The surface transforms with light and movement, creating voids, flashes, optical mixes, and moments of suspense. If observed long enough, the colours become intoxicating and hallucinatory; their shadow imprints on the retina like white noise in space, setting in motion a process of transcendence similar to that caused by ambient music and drone. Stewart grew up playing different instruments including the organ, piano, sax, accordion, and bass. Before exhibiting in galleries, her paintings were presented in music venues. Stewart’s process involves layering brush strokes and repetitive marks over underpainting, often in contrast to the final layer. The works echo the minimalist tradition of ‘color field’, particularly Ad Reinhardt’s signature black paintings, where colour became a subject in and of itself. Stewart’s paintings become visualisations rather than representations; they are not only objects to look at, but to look with. Gazing intently at the paintings may reveal a multitude of stories. Frag (2025) recalls the hedonistic influences of Fragonard’s Rococo; Troche (2025), a pictorial study of the pigment Rose Madder, derived from madder roots and highly sensitive to light, conjures Egyptian tombs, the ruins of Pompeii, and J.M.W. Turner’s eerie landscapes. Other ‘black studies’ evoke voids and theatrical backdrops. As the artist asks: ‘Why can’t we see the world as pure matter, pure form, pure gesture? […] Is it language that holds us back?’

___

Giulia Civardi is a curator and writer working both independently and, since 2020, as Curator & Collection Manager at Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation. She curated projects for institutions including Tate Modern, Rupert Centre for Art and Education, Kunstraum London and galleries including Gianni Manhattan for Curated by Vienna, Clima in Milan, Galerie In Situ in Paris, Madragoa in Lisbon. She regularly gives lectures and talks, and has guest lectured at Central Saint Martins, Goldsmiths University, Barbican Centre, Academy of Fine Arts Venice. She is an activist of AWI Art Workers Italia. Her writing on art and culture has been published, among the others, by NERO, Flash Art, CURA, this is tomorrow.

Denzil Forrester

Denzil Forrester

Untitled, 2019

Charcoal and pastel on paper

59.5 x 84cm. Framed: 77.7 x 102.5cm.

Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York

Photo: Todd-White Art Photography Denzil Forrester

Denzil Forrester

Red Stripe, 1982

Compressed charcoal and pastel on paper

56 x 76cm. Framed: 74.6 x 94.8cm

Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

Photo: Todd-White Art Photography. Denzil Forrester

Denzil Forrester

Night Strobe, 1984

Pencil and compressed charcoal on paper

56 x 76cm. Framed: 75.4 x 95.4cm

Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

Photo: Todd-White Art Photography. Denzil Forrester

Denzil Forrester

Night Star, 1983

Pastel on paper

41.8 x 60cm. Framed: 64 x 83cm

Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York

Photo: Todd-White Art Photography Denzil Forrester

Denzil Forrester

Dub Dance, 1993

Oil on board, 123.2 x 185cm

Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

Photo: Mark Blower Denzil Forrester

Denzil Forrester

Boom Boom Echoes, 2023

Oil on canvas, 203 x 274.5cm

Courtesy the artist and Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

Photo: Todd-White Art Photography Phoebe Collings-James

Phoebe Collings-James

Joy comes with the morning [V3], 2025

stoneware ceramic bowl, rope, sound

Dimensions variable

Courtesy of the Artist and Arcadia Missa, London

Photo: Andrea Rossetti Phoebe Collings-James

Phoebe Collings-James

Infidel [blue blurrr fire], 2025

Glazed stoneware ceramic

78 × 23 × 23 cm

Courtesy of the Artist and Arcadia Missa, London

Photo: Andrea Rossetti Phoebe Collings-James

Phoebe Collings-James

The Guardian, 2023

Stoneware glazed ceramic

51 x 58.5 cm

Courtesy of the Artist and Arcadia Missa, London

Photo: Josef Konczak Phoebe Collings-James

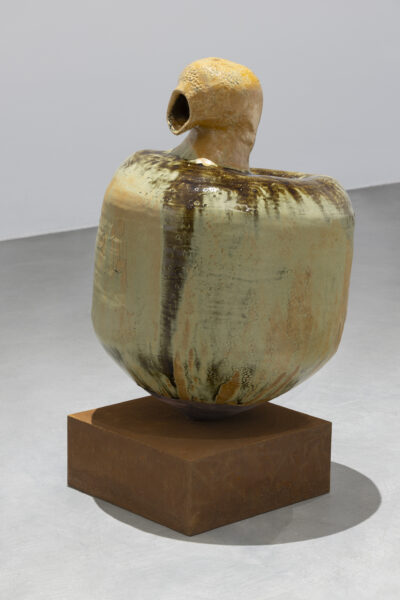

Phoebe Collings-James

The Infidel, 2023

Stoneware slip ceramic on a steel base

45 x 25 cm

Stand: 18 x 18 cm

Courtesy of the Artist and Arcadia Missa, London

Photo: Josef Konczak MININI_WORKS_0Phoebe Collings-James

MININI_WORKS_0Phoebe Collings-James

Infidel [eye], 2024

Glazed stoneware ceramic on a steel base

59 x 39 x 42 cm

Commissioned by SculptureCenter, New York

Photo: Andrea Rossetti Phoebe Collings-James

Phoebe Collings-James

Infidel [KING], 2024

Brass, glazed ceramic

46 x 56 x 48 cm

Commissioned by SculptureCenter, New York

Photo: Charles Benton Kate Spencer Stewart

Kate Spencer Stewart

Troche, 2025

Oil on linen sized with rabbit skin glue

56 × 56 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London

Photo: Marten Elder Kate Spencer Stewart

Kate Spencer Stewart

Terme, 2025

Oil and tempera on linen sized with rabbitskin glue

35 × 35 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London

Photo: Marten Elder Kate Spencer Stewart

Kate Spencer Stewart

Phthaloish, 2025

Oil on linen

110 x 110 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London

Photo: Marten Elder Kate Spencer Stewart

Kate Spencer Stewart

Frag, 2024

Oil on linen

35 × 35 cm

Courtesy of the artist and Emalin, London

Photo: Marten Elder