Opening 29/03 - 29/03 - 29/04, 2017

-

Armin Boehm

Intimacy and Vulnerability

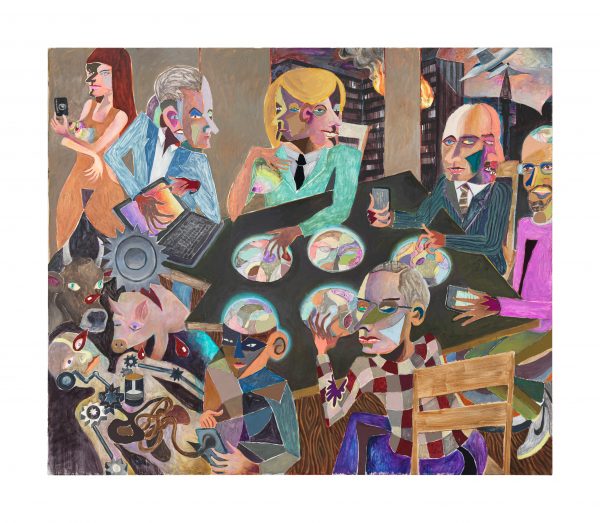

In “Brain Manipulation Conference” a party of mighty men sits at a table. At first sight, it seems they are having dinner together. But on the table, instead of the plates, there are holes through which one looks directly at human brains.

A minaret, a warplane and a Jewish star stand out in the background, an apparent suggestion of the Middle East conflict. The characters under the table only look human, while in the inside, instead of organs, they are made up of mechanical parts. Nearby, a saw horribly lacerates two animals.

The grotesquely distorted double faces allude, even without accuracy in the portraits, to Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, Vladimir Putin or Bashar al-Assad.

Armin Boehm’s art is stylistically influenced by the 1920s Expressionism as well as by the fabric collages typical of Arte Povera. The association, for example, with the “Pillars of society”, through which George Grosz set up as a satirical criticism of the society in the Weimar Republic, is quite intentional. In the same way, Boehm’s picture looks at the menacing political conflicts of our time. Yet Boehm is not a mere political painter. Rather, he portrays in his dreamy, surreal sceneries visions and fears not only universally dominant but also personal.

Sometimes the artist processes his own dreams. Human body, seen in its vulnerability, plays a central role in all his images. In this picture, the mighty are portrayed while materially manipulating human brains, as a metaphor for a “brainwashing” carried out also by unilateral media coverage and conscious “fake news”.

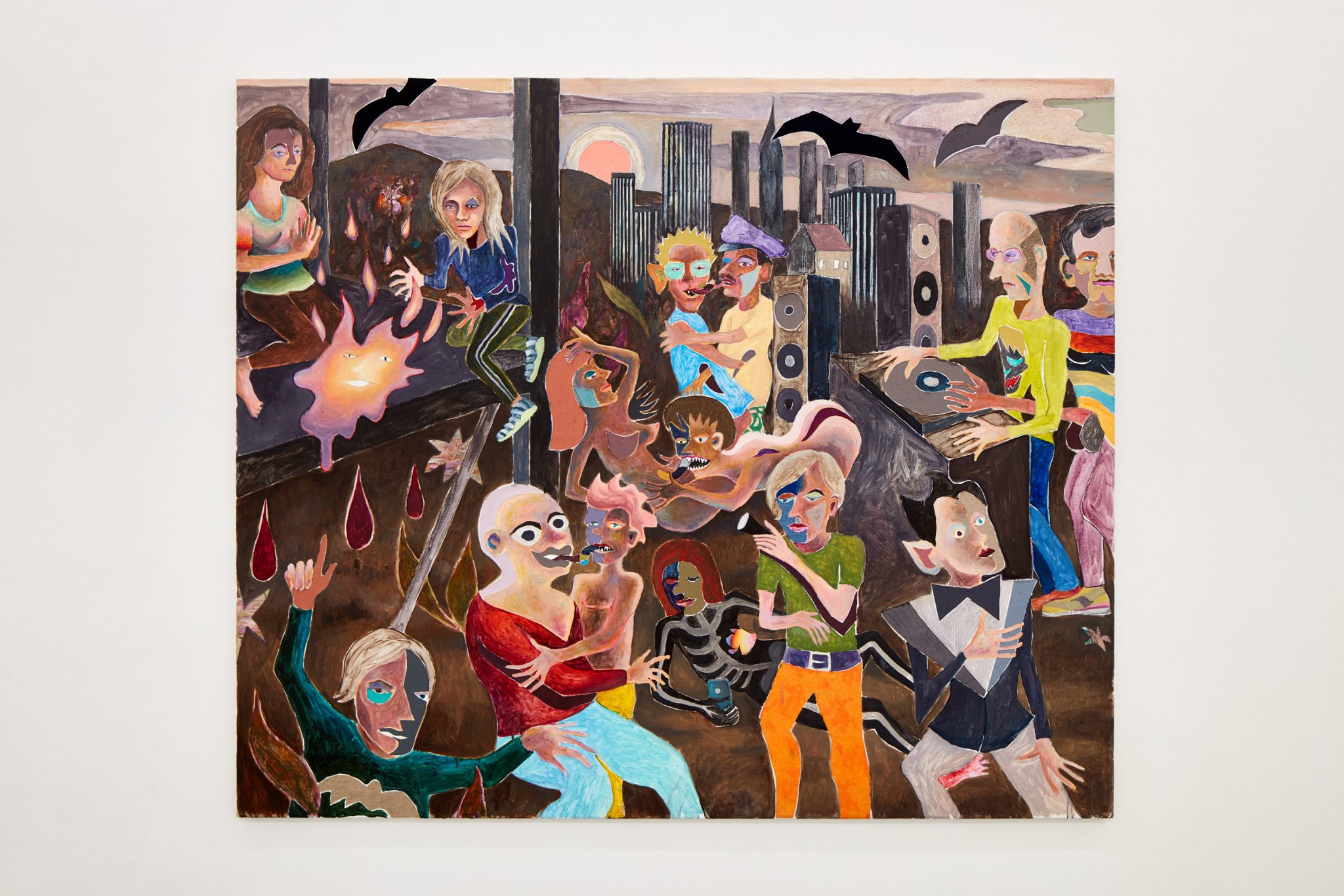

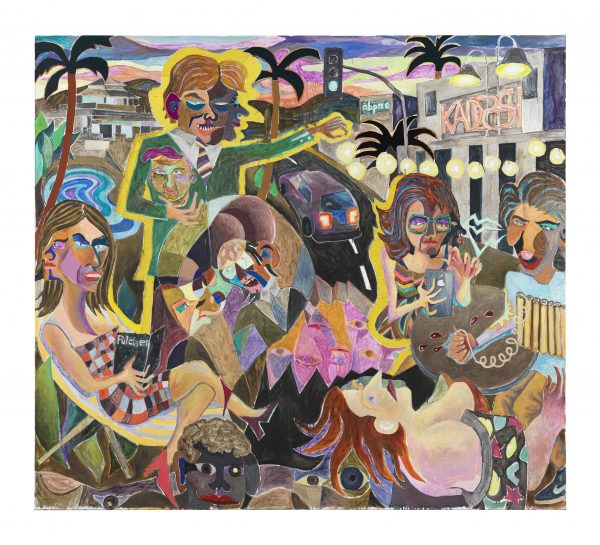

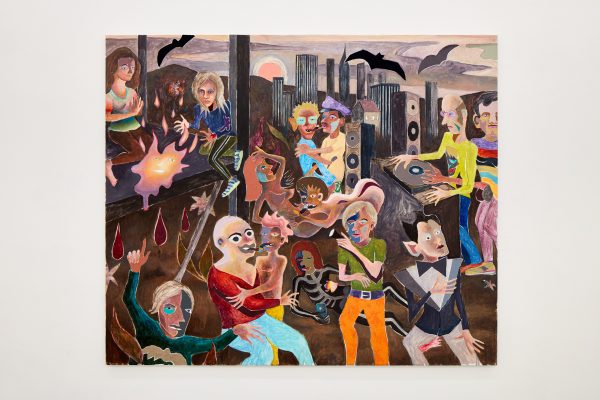

Armin Boehm’s art can be placed in the modern tradition of a sceptical view of the positive and also technical utopias. One of the central motifs of this dark Modernity is the attacked, dismembered or destroyed body, the “Body in Pieces”, which art historian Linda Nochlin analyzed as a “metaphor of modernity”. Refusing abstraction, Boehm brings narrative directly on the stage. A “different” Modernity is also the one represented by the gay-lesbian communities, to which Armin Boehm with the “Queer Orgy” pays homage. Leigh Bowery, Freddie Mercury, Klaus Nomi, Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith are in the party, and the DJ on the desk is the philosopher Michel Foucault. But behind the exuberant party lurk illness and death. Many of the celebrities died of AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s.

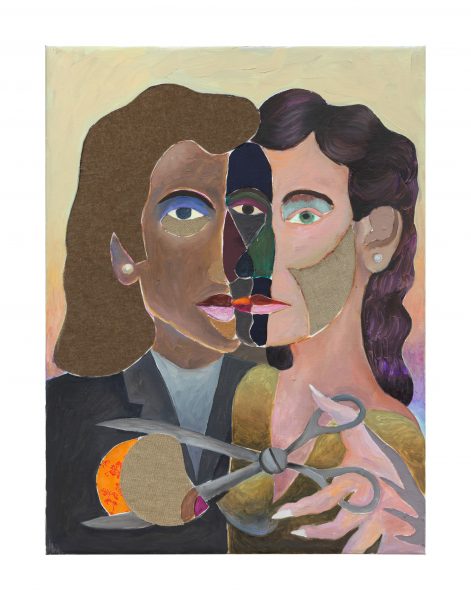

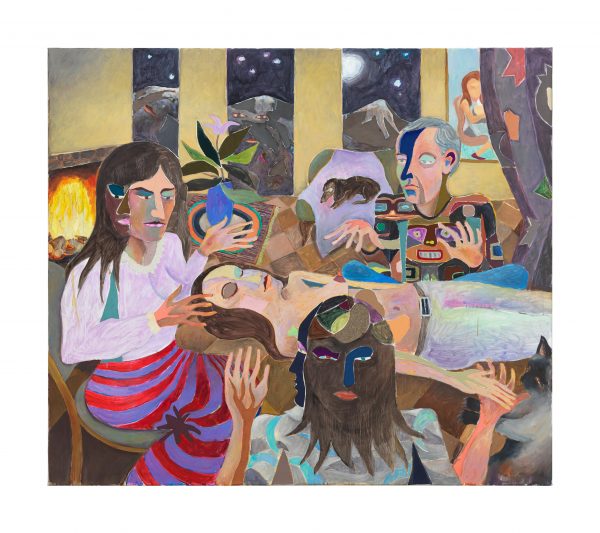

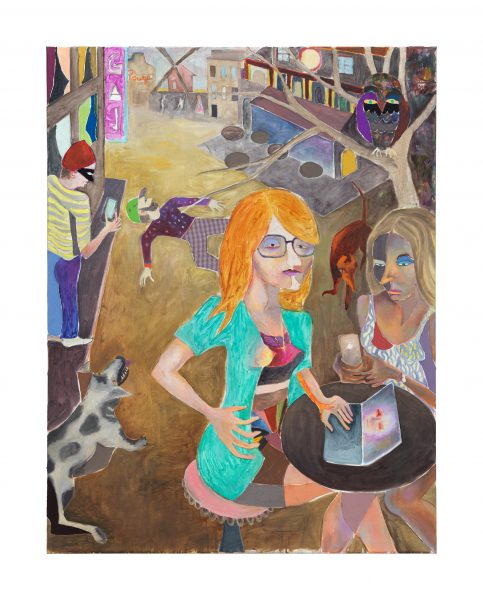

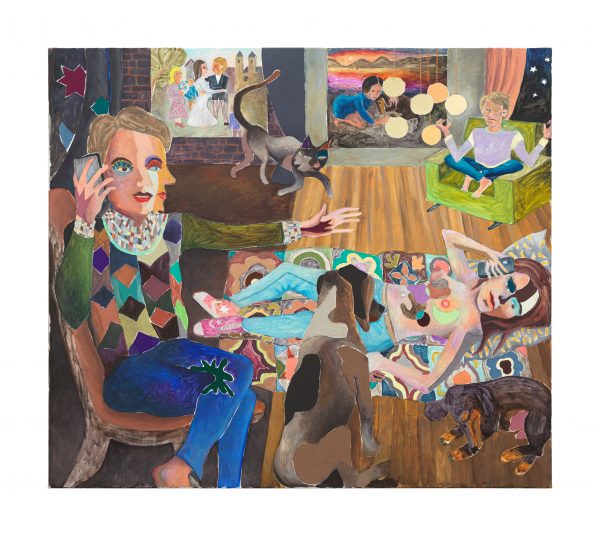

In the rather autobiographical healing images a rather pessimistic mood is replaced by a conscious, naive positivity, which is new in the work of Armin Boehm. The pastel, soft colours and the playful ornamentation are supposed to produce effects reminding at Joseph Beuys’ idea of ”healing through art”. The human figure, often painted with a second face, does not show any threatening manipulations or penetrations in these works, but seems to have positive magical abilities. The double-face not only appears as a motif, but also metaphorically shapes the overall exhibition. On the one hand the surface is often brittle and rough, emphasizing the physical, concrete quality of colour. On the other bright, intense colours strongly differ from the darker palette that was a mark of the earlier phases of Armin Boehm’s work.

Ludwig Seyfarth

In “Brain Manipulation Conference” a party of mighty men sits at a table. At first sight, it seems they are having dinner together. But on the table, instead of the plates, there are holes through which one looks directly at human brains.

A minaret, a warplane and a Jewish star stand out in the background, an apparent suggestion of the Middle East conflict. The characters under the table only look human, while in the inside, instead of organs, they are made up of mechanical parts. Nearby, a saw horribly lacerates two animals.

The grotesquely distorted double faces allude, even without accuracy in the portraits, to Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton, Vladimir Putin or Bashar al-Assad.

Armin Boehm’s art is stylistically influenced by the 1920s Expressionism as well as by the fabric collages typical of Arte Povera. The association, for example, with the “Pillars of society”, through which George Grosz set up as a satirical criticism of the society in the Weimar Republic, is quite intentional. In the same way, Boehm’s picture looks at the menacing political conflicts of our time. Yet Boehm is not a mere political painter. Rather, he portrays in his dreamy, surreal sceneries visions and fears not only universally dominant but also personal.

Sometimes the artist processes his own dreams. Human body, seen in its vulnerability, plays a central role in all his images. In this picture, the mighty are portrayed while materially manipulating human brains, as a metaphor for a “brainwashing” carried out also by unilateral media coverage and conscious “fake news”.

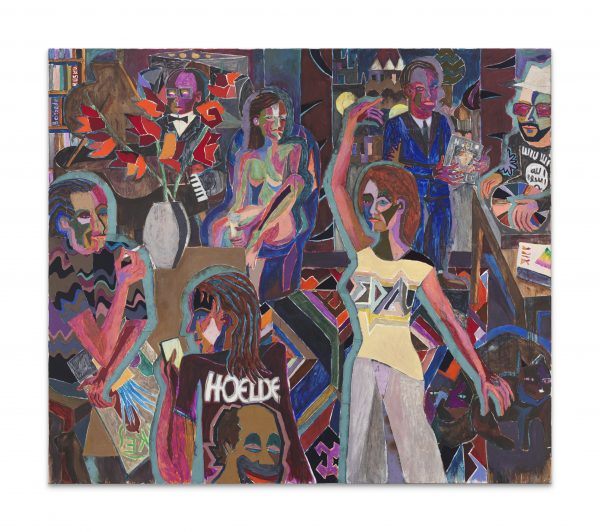

Armin Boehm’s art can be placed in the modern tradition of a sceptical view of the positive and also technical utopias. One of the central motifs of this dark Modernity is the attacked, dismembered or destroyed body, the “Body in Pieces”, which art historian Linda Nochlin analyzed as a “metaphor of modernity”. Refusing abstraction, Boehm brings narrative directly on the stage. A “different” Modernity is also the one represented by the gay-lesbian communities, to which Armin Boehm with the “Queer Orgy” pays homage. Leigh Bowery, Freddie Mercury, Klaus Nomi, Robert Mapplethorpe and Patti Smith are in the party, and the DJ on the desk is the philosopher Michel Foucault. But behind the exuberant party lurk illness and death. Many of the celebrities died of AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s.

In the rather autobiographical healing images a rather pessimistic mood is replaced by a conscious, naive positivity, which is new in the work of Armin Boehm. The pastel, soft colours and the playful ornamentation are supposed to produce effects reminding at Joseph Beuys’ idea of ”healing through art”. The human figure, often painted with a second face, does not show any threatening manipulations or penetrations in these works, but seems to have positive magical abilities. The double-face not only appears as a motif, but also metaphorically shapes the overall exhibition. On the one hand the surface is often brittle and rough, emphasizing the physical, concrete quality of colour. On the other bright, intense colours strongly differ from the darker palette that was a mark of the earlier phases of Armin Boehm’s work.

Ludwig Seyfarth

The Open Eyes of the Death, 2017oil and fabric on canvas

The Open Eyes of the Death, 2017oil and fabric on canvas

210×235 cm Vision of a Queer Orgy, 2017Oil and fabric on canvas

Vision of a Queer Orgy, 2017Oil and fabric on canvas

160×190 cm Gender Confusion, 2017oil and fabric on canvas

Gender Confusion, 2017oil and fabric on canvas

80×60 cm The good spirits of the Alps, 2017oil and fabric on canvas

The good spirits of the Alps, 2017oil and fabric on canvas

130×150 cm Bataclan Skypers, 2017oil and fabric on cavas

Bataclan Skypers, 2017oil and fabric on cavas

130×100 cm The Animal Healing, 2017oil and fabric on canvas

The Animal Healing, 2017oil and fabric on canvas

140×160 cm The Brain Manipulation Conference, 2017oil and fabric on canvas

The Brain Manipulation Conference, 2017oil and fabric on canvas

170×200 cm Tanzen zu fremder Musik (Dancing to a strange music), 2016oil and fabric on canvas

Tanzen zu fremder Musik (Dancing to a strange music), 2016oil and fabric on canvas

200×230 cm