22/01 - 11/02, 2015

-

Deborah Ligorio

Accessories in Algorithmic Gardens

For her solo show at Francesca Minini, Deborah Ligorio presents a series of portraits based on the calculation of the individual carbon footprint from a group of friends and friends of friends. Prior to the opening of the show, the gallery will be hosting a workshop from the series [ the Eponym ]: on lifelogging, nature-culture, and body exercises. As a discursive event some elements from the workshop will remain on display for the show, such as the sequence of short trailers, brief videos of around half a minute or less, that virtually accompany the workshop.

The show explores the dynamic and complex nature of scientific practices; it observes its economies of profit and loss. The profile of a person based on their data is used by IT industry to market customized products. Such portraits are constantly generated by social networks. The show examines and observes the way in which the materiality of our embodiment and the measuring tools we use to observe, understand and describe the world determine our very perception of it.

One example is global warming: we know that it is happening thanks to scientific modeling, yet the perceptible effects are only directly causal. At the same time the very measures we decide to take are themselves the result of a scientific way of looking at things. In order to calculate the C02 emissions for the works in the exhibition the artist made use of a tool available online. The multiple-choice system results as a boundary-making tool that is in itself formative of a behavioral standard. As it does not take into account important behavioral nuances. It seems clear that this, like other similar tools, is optimized for the life system of the western world. The show places itself in a dialectical negotiation of the boundaries, limits and materiality produced by the tool or apparatus used. The term “Apparatus”, according to the theorist Karen Barad, indicates “specific material-discursive practices (they are not merely laboratory setups that embody human concepts and take measurements); apparatuses produce differences that matter. They are boundary-making practices that are formative of matter and meaning, productive of, and part of, the phenomena produced”.

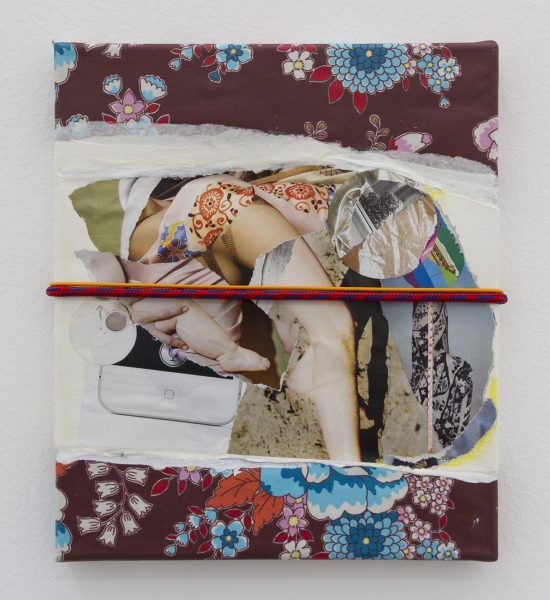

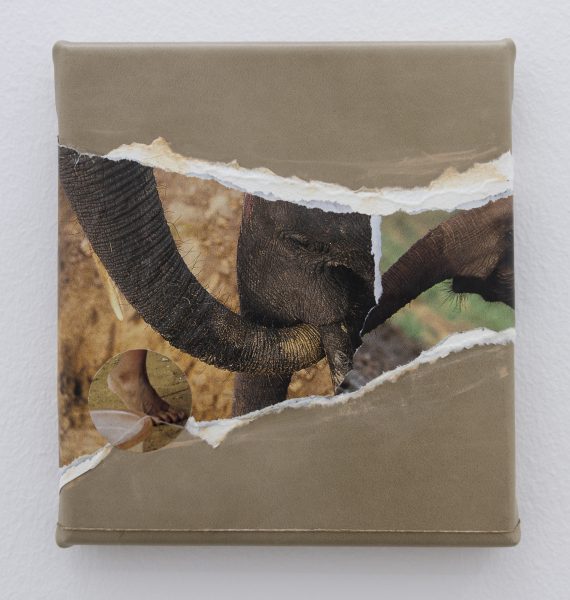

Deborah Ligorio, with the series of portraits from the data on carbon emissions, has realized a series of visualizations: small-format canvases, the result of the translation of the data and the observation of quantitative and qualitative aspects of the habits of the subjects portrayed. The canvases mix collages and acrylics on various materials. These materials used as backdrops are mounted onto looms, and chosen each time to describe the characteristics of the person portrayed. A string wrapped around the canvases corresponds to the amount of travels; the calculation was done over a period of one year.

The interface, or the magnitude that we use to look at the world can also be defined as scale. As the environmental historian Marco Armiero writes, “ [ … ] the scale we choose to adopt changes the way in which we understand problems and frame solutions. Let’s consider, for instance, certain severe environmental regulations which, applied in rich countries, have simply produced the shift of dangerous productions to poor countries with weaker environmental laws, in what is called ‘environmental dumping’. Likewise, polluting substances which are banned in the North are often still allowed in the global South’.”

The same system of knowledge that uses these separations, at the same time provides the scientific tools with which to visualize the planet as an ecosystem, where all of its parts are interconnected, even though this aspect is widely denied by the policy of only taking care of one’s own garden.

The theorist Timothy Morton states: “Unlike Latour, I do believe that we have “been modern,” and that this has had effects on human and nonhuman beings. […]

Now we know where it goes. For some time we may have thought that the U-bend in the toilet was a convenient curvature of ontological space that took whatever we flush down it into a totally different dimension called Away, leaving things clean over here. Now we know better: instead of the mythical land Away, we know the waste goes to the Pacific Ocean or the wastewater treatment facility. Knowledge of the hyperobject Earth, and of the hyperobject biosphere, presents us with viscous surfaces from which nothing can be forcibly peeled.”

The show is based on the premise that the same connectivity and the same impossibility of disentangling human and non-human lives, animate and inanimate worlds, the intertwinings of material objects and immaterial data. That same viscosity is indeed what links the infinity of data in this expanse of algorithmic gardens and the materiality of which we become accessories.

Special thanks to: Stefania Galegati, Massimo Grimaldi, Paul Keil, and Caleb Waldorf.

For her solo show at Francesca Minini, Deborah Ligorio presents a series of portraits based on the calculation of the individual carbon footprint from a group of friends and friends of friends. Prior to the opening of the show, the gallery will be hosting a workshop from the series [ the Eponym ]: on lifelogging, nature-culture, and body exercises. As a discursive event some elements from the workshop will remain on display for the show, such as the sequence of short trailers, brief videos of around half a minute or less, that virtually accompany the workshop.

The show explores the dynamic and complex nature of scientific practices; it observes its economies of profit and loss. The profile of a person based on their data is used by IT industry to market customized products. Such portraits are constantly generated by social networks. The show examines and observes the way in which the materiality of our embodiment and the measuring tools we use to observe, understand and describe the world determine our very perception of it.

One example is global warming: we know that it is happening thanks to scientific modeling, yet the perceptible effects are only directly causal. At the same time the very measures we decide to take are themselves the result of a scientific way of looking at things. In order to calculate the C02 emissions for the works in the exhibition the artist made use of a tool available online. The multiple-choice system results as a boundary-making tool that is in itself formative of a behavioral standard. As it does not take into account important behavioral nuances. It seems clear that this, like other similar tools, is optimized for the life system of the western world. The show places itself in a dialectical negotiation of the boundaries, limits and materiality produced by the tool or apparatus used. The term “Apparatus”, according to the theorist Karen Barad, indicates “specific material-discursive practices (they are not merely laboratory setups that embody human concepts and take measurements); apparatuses produce differences that matter. They are boundary-making practices that are formative of matter and meaning, productive of, and part of, the phenomena produced”.

Deborah Ligorio, with the series of portraits from the data on carbon emissions, has realized a series of visualizations: small-format canvases, the result of the translation of the data and the observation of quantitative and qualitative aspects of the habits of the subjects portrayed. The canvases mix collages and acrylics on various materials. These materials used as backdrops are mounted onto looms, and chosen each time to describe the characteristics of the person portrayed. A string wrapped around the canvases corresponds to the amount of travels; the calculation was done over a period of one year.

The interface, or the magnitude that we use to look at the world can also be defined as scale. As the environmental historian Marco Armiero writes, “ [ … ] the scale we choose to adopt changes the way in which we understand problems and frame solutions. Let’s consider, for instance, certain severe environmental regulations which, applied in rich countries, have simply produced the shift of dangerous productions to poor countries with weaker environmental laws, in what is called ‘environmental dumping’. Likewise, polluting substances which are banned in the North are often still allowed in the global South’.”

The same system of knowledge that uses these separations, at the same time provides the scientific tools with which to visualize the planet as an ecosystem, where all of its parts are interconnected, even though this aspect is widely denied by the policy of only taking care of one’s own garden.

The theorist Timothy Morton states: “Unlike Latour, I do believe that we have “been modern,” and that this has had effects on human and nonhuman beings. […]

Now we know where it goes. For some time we may have thought that the U-bend in the toilet was a convenient curvature of ontological space that took whatever we flush down it into a totally different dimension called Away, leaving things clean over here. Now we know better: instead of the mythical land Away, we know the waste goes to the Pacific Ocean or the wastewater treatment facility. Knowledge of the hyperobject Earth, and of the hyperobject biosphere, presents us with viscous surfaces from which nothing can be forcibly peeled.”

The show is based on the premise that the same connectivity and the same impossibility of disentangling human and non-human lives, animate and inanimate worlds, the intertwinings of material objects and immaterial data. That same viscosity is indeed what links the infinity of data in this expanse of algorithmic gardens and the materiality of which we become accessories.

Special thanks to: Stefania Galegati, Massimo Grimaldi, Paul Keil, and Caleb Waldorf.

Aldo, Palermo, friend of Stefania, carbon emission 8.33 Tons per year, 2015

Aldo, Palermo, friend of Stefania, carbon emission 8.33 Tons per year, 2015

mixed media

25×21 cm Savitri, Palermo, friend of Stefania, carbon emission 3.93 Tons per year, 2015

Savitri, Palermo, friend of Stefania, carbon emission 3.93 Tons per year, 2015

mixed media

39×35 cm Anonymous Them, Syndey, data retrieved online, carbon emission 10.67 Tons per year, 2014

Anonymous Them, Syndey, data retrieved online, carbon emission 10.67 Tons per year, 2014

mixed media

39×33 cm Namarig, Port Sudan, friend of Massimo, carbon emission 5.63 Tons per year, 2014mixed media

Namarig, Port Sudan, friend of Massimo, carbon emission 5.63 Tons per year, 2014mixed media

30×26 cm Markus, Beijing, friend, carbon emission 14.98 Tons per year, 2014mixed media

Markus, Beijing, friend, carbon emission 14.98 Tons per year, 2014mixed media

34×31 cm Christiane e Volkmar, Brackenheim, Germany, Relatives, carbon emission 5.09 and 11.61 Tons per year, 2015

Christiane e Volkmar, Brackenheim, Germany, Relatives, carbon emission 5.09 and 11.61 Tons per year, 2015

mixed media

40×36 cm Anonymous, Saint-Denis, La Réunion, data retrieved online, carbon emission 3.91 Tons per year, 2015

Anonymous, Saint-Denis, La Réunion, data retrieved online, carbon emission 3.91 Tons per year, 2015

mixed media

32×30 cm Dylan, Austin, Texas, Relative of Caleb, carbon emission 21.06 Tons per year, 2015

Dylan, Austin, Texas, Relative of Caleb, carbon emission 21.06 Tons per year, 2015

mixed media

42×35 cm Tiziana, New York city, Relative, carbon emission 5.27 Tons per year, 2014

Tiziana, New York city, Relative, carbon emission 5.27 Tons per year, 2014

mixed media

30×26 cm Anonymous, Village Close to Guwahati, Assam, India, friend of Paul, carbon emission 0.65 Tons per year, 2015

Anonymous, Village Close to Guwahati, Assam, India, friend of Paul, carbon emission 0.65 Tons per year, 2015

mixed media

20×18 cm Anonymous, Detroit, data retrieved online, carbon emission 7.41 Tons per year, 2015

Anonymous, Detroit, data retrieved online, carbon emission 7.41 Tons per year, 2015

mixed media

39×32 cm